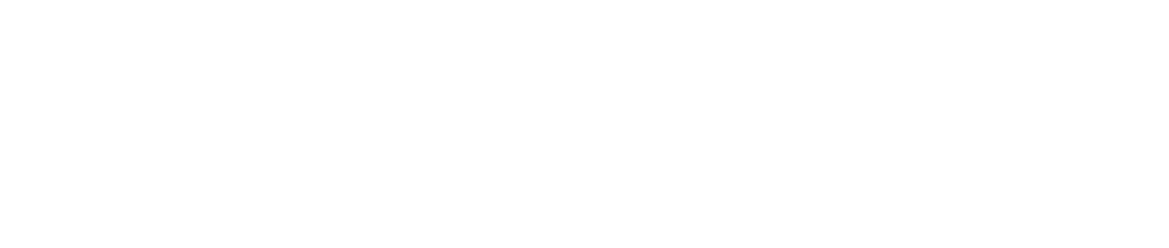

From Baboquivari Peak to the Bradshaw Mountains, Coffee or Die Magazine spent time with rescuers from the US Department of Homeland Security's Air and Marine Operations and the Yavapai County Sheriff’s Backcountry Search and Rescue Unit. Coffee or Die Magazine composite.

BABOQUIVARI PEAK WILDERNESS, Arizona — And there was Baboquivari Peak, rising like a cloud-scraping angel, her flint wings veined in gold and unfurled above a ridge of lesser mountains, all of them draped in her black shadow.

The peak is the queen of the mountains here, and the smaller spires fall in line like her pawns on a chessboard that runs down the Tohono O’odham Nation and then into Mexico.

South of the international boundary, the ridgeline becomes the Pozo Verde Mountains. They’re what US Customs and Border Protection Air and Marine Operations Air Interdiction Agent Zoe Cunningham squinted at from the cockpit of her Eurocopter AS-350L AStar helicopter.

It was Sept. 6, and monsoons had painted long treks of the Sonoran Desert green. But regardless of the terrain’s color, under the sun and above the rock, hidden by elephant trees and honey mesquite, smugglers were avoiding Cunningham and her helicopter.

Baboquivari Peak rises majestically from the Baboquivari Peak Wilderness, a 2,065-acre wilderness area located roughly 50 miles southwest of Tucson, Arizona. It's surrounded by the sprawling Tohono O'odham Nation. Photo by Noelle Wiehe/Coffee or Die Magazine.

Mexican foot guides — called coyotes — were bringing in people, increasingly undocumented migrants from Guatemala, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Honduras. Somewhere near them were other men muscling bales of marijuana and bags of narcotics over the hills and across the desert pan. All of them were dodging rip crews, heavily armed gangs poised to ambush traffickers along the crags or on the playas.

They make their bones stealing drugs or shaking down migrants for the pesos in their pockets.

Sometimes American tourists become unsuspecting extras in this underworld drama playing out inside the Baboquivari Peak Wilderness, like the exhausted family Cunningham recently plucked from the highlands here.

“I don't think they really knew that this is a highly trafficked area,” the pilot told Coffee or Die Magazine.

Air Interdiction Agent Zoe Cunningham refuels in the Sonoran Desert in southern Arizona on Sept. 6, 2022. Photo by Noelle Wiehe/Coffee or Die Magazine.

She pointed to a line scraped across a ridge, about 7,000 feet above sea level. Even if a rock slide buries the path, the stones and shards are slowly ground into dust again and again, thanks to thousands of boots and sneakers carrying desperate people north toward Tucson or Phoenix.

“You can see a little tiny foot trail that looks like a hiking trail, and it's just like right on the very top,” she said. “It’s a tiny dirt trail that snakes all the way along. That’s not a hiking trail. That's from the sheer number of migrants coming up through here. They have established this trail.”

Cunningham is the federal government’s eyes in the skies. She knows where coyotes try to hide and where migrants are most likely to die of thirst or exposure, whether they’re on this path or they’re summiting a mountain.

And she knows crime syndicates south of the border pay scouts to watch her helicopter, too. So she figured we were being observed by men with satellite phones.

Air Interdiction Agent Zoe Cunningham prepares to fly her Eurocopter AS-350L AStar helicopter over the Baboquivari Mountains in southern Arizona. Photo by Noelle Wiehe/Coffee or Die Magazine.

Her helicopter skirted over a spot in the Peck Canyon near Rio Rico where a rip crew armed with AK-47s had gunned down US Border Patrol Agent Brian Terry on Dec. 15, 2010. She can see his memorial from the sky, and it’s a daily reminder to her about the risks law enforcement runs in the desert.

“Are you close enough? Do you want me to come down low? Do you want me to make my presence known?” Cunningham asked, ticking off what she and her aircraft offer to agents on the ground.

She’ll also drop food, water, and other supplies. It’s often what keeps migrants alive long enough for rescuers to reach them on foot, by horse, or by truck.

Over the past four years, Air and Marine Operations hassaved 1,359 lives across the US border with Mexico.

Smoke rises over the Sonoran Desert as Air Interdiction Agent Zoe Cunningham flies her Eurocopter AS-350L AStar helicopter in southern Arizona on Sept. 6, 2022. Photo by Noelle Wiehe/Coffee or Die Magazine.

They’ve also stopped 774,025 kilograms of illegal drugs from entering the US. Roughly half of that’s marijuana, the rest a mix of cocaine, methamphetamine, heroin, and fentanyl, according to US Department of Homeland Security reports.

Drug interdiction is important, but Alexander Zamora, the US Army veteran who supervises Air and Marine Operations in Tucson, said saving migrant lives from the desert that’s constantly trying to kill them remained a top mission.

“We're here as a very interesting mix between law enforcement and aviation,” he said. “That's the one thing that has always been interesting to see through the years.”

Zamora told Coffee or Die he got emergency calls from the Arizona Air Coordination Center daily, but Cunningham and his other pilots often found themselves assisting rescuers who weren’t in law enforcement.

Volunteers with the Yavapai County Sheriff’s Backcountry Search and Rescue Unit practice saving lives on Sept. 10, 2022, in Arizona. Photo by Noelle Wiehe/Coffee or Die Magazine.

Under Arizona law, each sheriff oversees most search and rescue operations in the state’s 15 counties. The majority of the rescuers are volunteers, and officials estimate they combine to save roughly 600 lives annually.

Josh Schmidt, a volunteer with the Yavapai County Sheriff’s Backcountry Search and Rescue Unit, told Coffee or Die the group had run 47 missions last year, roughly five to seven every month.

That was about half the number of missions he ran in 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic prodded more hikers to hit the hills.

“We always look at it as, if that was my loved one, that was my family member, I would want someone to go out and bring them home,” said Schmidt, an anatomy and physiology instructor at Yavapai College.

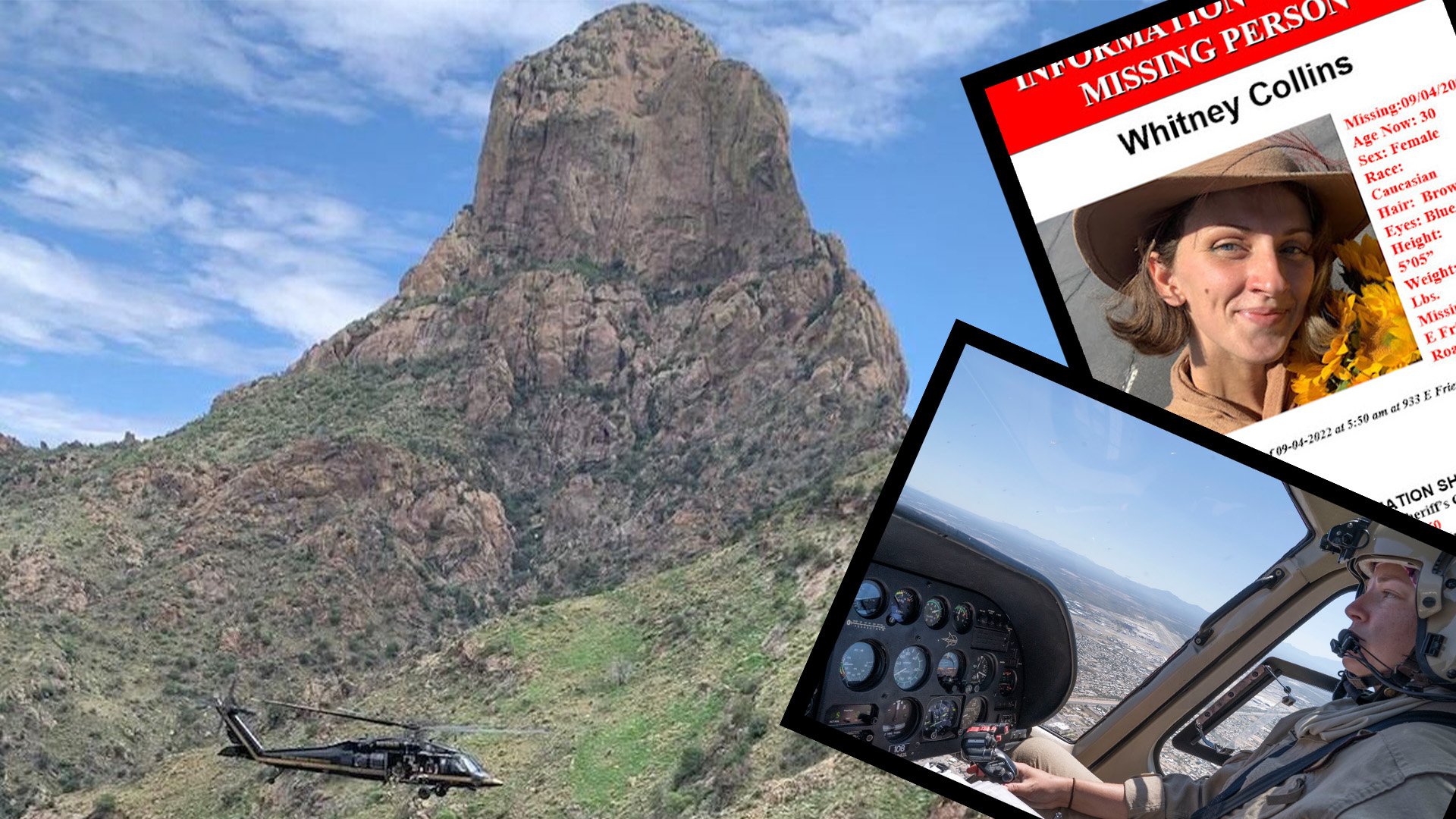

When Coffee or Die met up with him, he and his fellow rescuers had just come off a three-day hunt for Whitney Collins. The 30-year-old Prescott woman disappeared Sept. 4 during her daily morning hike near the Bradshaw Mountains.

On Sept. 4, 2022, the Yavapai County Sheriff’s Office released a photo of a missing person, Whitney Collins, who was last seen on East Friendly Pines Road in Yavapai County, Arizona. Yavapai County Sheriff’s Office photo.

They lugged their 30-pound packs across 100 square miles of brush and highlands, under ponderosa pines and over sun-blasted boulders, slowly expanding the search radius from where the woman’s footprints vanished near Friendly Pines Road.

“We go to the place the person was last seen, and we try to determine if we can find out what kind of shoes are they wearing,” said Dan Dravis, a mechanical engineer who’s volunteered on rescues for 18 years. “What size shoes do they wear? What do they typically do?’”

And then authorities suddenly called off the search and announced Collins was never really lost. They’ve declined to detail where she’d been the whole time while Dravis hiked the backcountry looking for her.

He shrugged it off as just another mission.

“There were a lot of resources expended. A lot of effort was put into it, but that's what we do,” Dravis said. “That’s our goal, is that everybody comes home. So, as long as that happens, we’re happy.”

Read Next: Prosecutors: Smuggler Threatened To Murder Federal Agent

Noelle is a former staff writer for Coffee or Die through a fellowship from Military Veterans in Journalism. She has a bachelor’s degree in journalism and interned with the US Army Cadet Command. Noelle also worked as a civilian journalist covering several units, including the 75th Ranger Regiment on Fort Benning, before she joined the military as a public affairs specialist.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.