Why Chris Ryan Credits Training for Survival of Longest Escape and Evasion in British SAS History

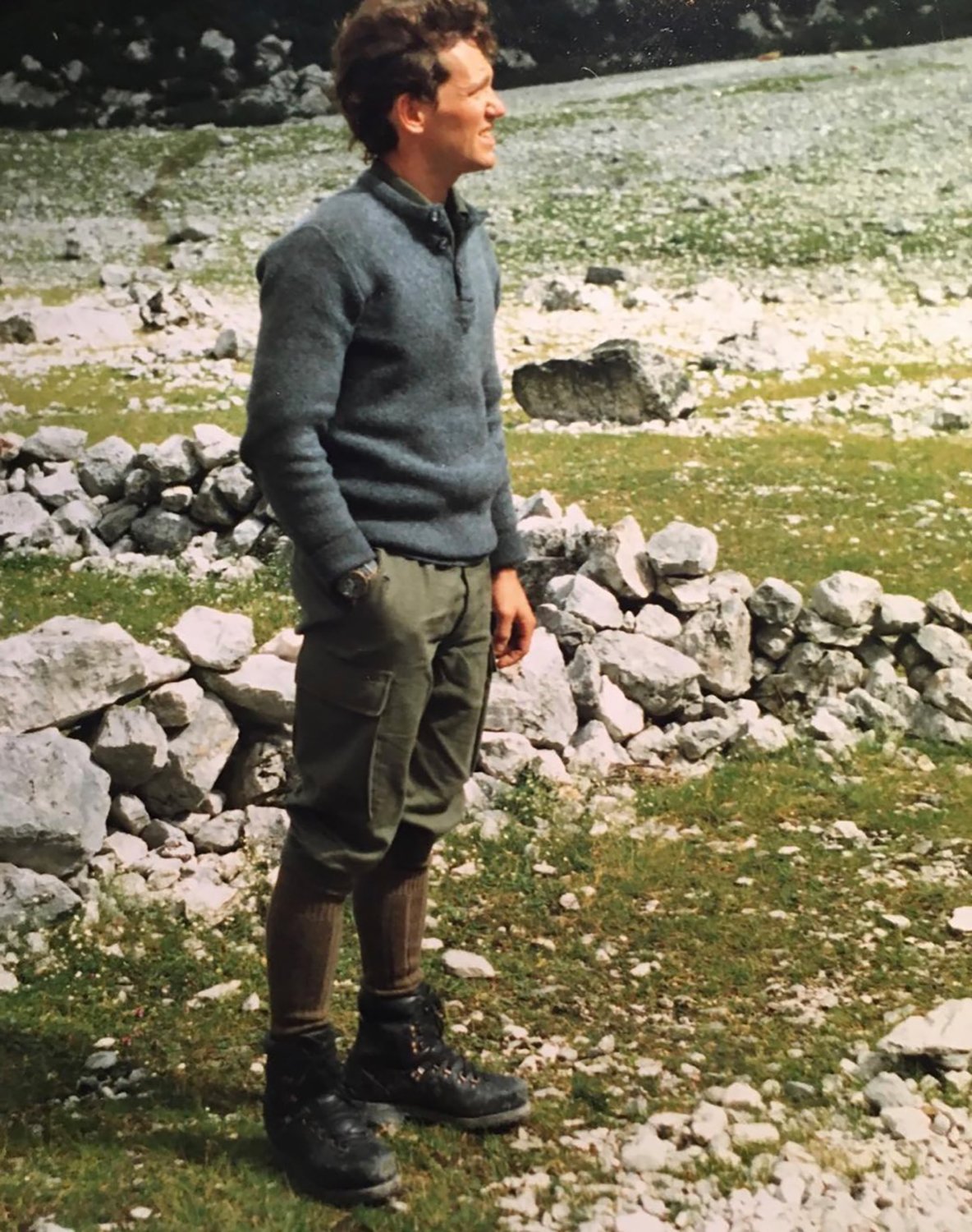

“German Alpine Guides Course, first six weeks I lived in that poxy tent!!” Chris Ryan writes on his Instagram. Photo courtesy of Chris Ryan/Instagram. Composite by Coffee or Die Magazine.

In January 1991, at the start of Operation Desert Storm, an eight-man British Special Air Service team under the call sign Bravo Two Zero was compromised while conducting a reconnaissance patrol north of Baghdad.

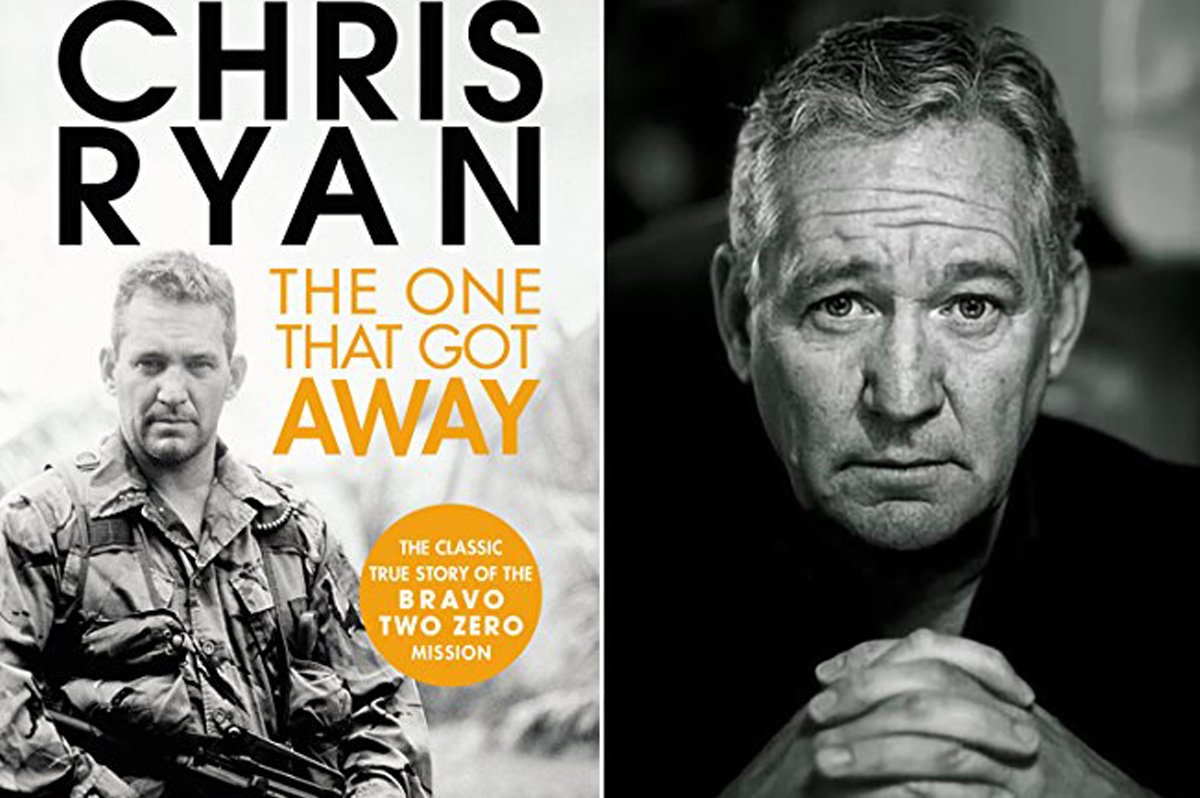

As the infamous story goes, the SAS commandos were discovered by a goat herder who informed a local militia of their presence. A battle ensued, and Bravo Two Zero eventually got split up. Cpl. Colin Armstrong, better known today by his pen name Chris Ryan, fled on foot for some 200 miles through the Iraqi desert until he reached the Syrian border — a harrowing eight-day journey that would go down as the longest escape and evasion in SAS history. He was the only member of the team to avoid capture and also survive.

Ryan served 10 years in the SAS, from 1984 to 1994. During that time, he worked in some of the world’s most rugged environments, places like Siberia and Mount Everest, but he said none were more unforgiving than the Iraqi desert. “I’d never experienced such pain from cold, such agony in spine and legs,” he recalled in his 1995 memoir, The One That Got Away: My SAS Mission Behind Enemy Lines. Why he survived the journey and some of his teammates didn’t is, of course, a question with no single answer; however, Ryan himself largely attributes his survival to his SAS training — and in particular, the training he received at the German Alpine Guide’s Course at the Mountain Warfare School in Mittenwald.

“They sent me to Germany for two years to become a guide,” Ryan told Coffee or Die Magazine. “My time in the SAS, if I wasn’t on a counterterrorism team, I was hanging on a rope on a mountain somewhere.”

The British SAS 22nd Regiment comprises four squadrons, and each of those has its own mountain troop. The alpine guide is essentially the troop’s resident expert on all things pertaining to high-altitude wilderness survival. For example, Ryan explained, “if there was an operation where a squadron had to come from a beachhead, and there’s a cliff — you’d be responsible for putting the fixed lines in, picking routes out. You’d be responsible for all the ski training, all the climb training, prediction of weather, avalanches, crossing glaciers.”

The Alpine Guide’s Course was conducted entirely in German, so Ryan also had to learn how to read and speak the language. The course lasted a total of 18 months, during which time he and his classmates underwent rigorous training in basic mountaineering, climbing, fixed lines, rescues, avalanche clearing, and skiing, among other things. He also learned how to identify the signs and symptoms of hypothermia — knowledge that would later prove crucial for him in the desert.

Upon completing the Alpine Guide’s Course, Ryan was assigned to a British SAS Special Projects team focused on counterterrorism operations. Several months later, Saddam Hussein’s army invaded Kuwait, and soon after, Ryan was deployed to the Gulf with B Squadron.

B Squadron’s mission, like many SAS missions, was clandestine in nature. Three eight-man teams, designated Bravo One Zero, Bravo Two Zero, and Bravo Three Zero, would be inserted by helicopter deep in the heart of Iraq. They would then proceed on foot to establish several observation posts where they would monitor enemy activity and look for SCUD missile sites. Heavily armed teams from A Squadron and D Squadron would be on standby to move in and destroy the sites once they were located.

Ryan later recalled that, on the eve of the mission, he was concerned about the team’s lack of cold-weather gear. Temperatures in the desert can fall below freezing at night. He was also worried about their ability to safely get off the objective in the event that they were compromised. Despite the fact that they would be operating behind enemy lines, Bravo Two Zero had no established escape and evasion plan, only basic instructions to either flee south in the direction of Saudi Arabia or west to the Iraqi-Syrian border.

Ryan’s fears were soon realized.

On the afternoon of Jan. 24, 1991, while Bravo Two Zero was hunkered down in a wadi to avoid being seen, one of his teammates was spotted by a young goat herder. Assuming their mission was compromised, Bravo Two Zero’s radio operator issued an emergency distress signal but on the wrong radio frequency, so the transmission never reached SAS headquarters. Then, two men armed with AK-47s appeared in the distance. Ryan raised his hand to wave and the men responded by opening fire. A truck carrying at least eight more militants arrived next, followed by another vehicle mounted with a .50-caliber machine gun. All hell broke loose. Outmanned and outgunned, Bravo Two Zero bounded in retreat, taking turns firing back at the enemy to cover their movements as they tried to break contact.

Upon reaching safer ground, the team huddled to plot their next move. They knew that, if their emergency signal had been successfully transmitted, a combat search and rescue helicopter would be inbound to pick them. But they also knew that the enemy would be lying in wait to ambush the helicopter crew. Waiting for help to arrive was too risky. So they decided instead to make their escape on foot. They would walk to the Syrian border, some 80 miles away, in single-file, and Ryan, as point man, would set the pace.

The commandos began their journey under the cover of darkness and walked through the night. Ryan activated his TACBE, a tactical beacon, attempting to contact friendly aircraft passing overhead, but to no avail. Then, headlights suddenly appeared in the distance behind them, and they knew they were being hunted. The desert terrain was flat, but the approaching vehicle had to move at a crawling speed to avoid going over the embankment of a wadi. Bravo Two Zero changed directions several times to make it more difficult for their pursuers to track them. Their aim was to reach the main supply route through northwest Iraq and then follow the road to higher ground en route to the border.

After pausing to regroup, Ryan stepped off again with the rest of Bravo Two Zero behind him, each man separated from the others by approximately 200 to 300 meters. After about an hour of walking, Ryan turned around and saw that only two of his teammates were still with him. The rest of Bravo Two Zero were gone.

Ryan and the two other commandos tried to contact the missing element over the radio, but an hour passed with no reply. So they decided to push onward, walking about 50 miles in the middle of the desert through the night, only stopping to check their position on the map. Just before dawn, the trio lay down against a tank berm, planning to rest there until the following night. Ryan drifted off to sleep, and when he awoke, the temperature had fallen below freezing and the weather quickly worsened with snowfall and rain.

Ryan had never experienced the kind of agony he felt from the frigid weather. From his lectures in training, he knew how to recognize the signs and symptoms of hypothermia: disorientation, dizziness, sudden mood swings, outbursts of anger, confusion, and drowsiness. Now, as he trudged through the desert, Ryan began to recognize some of those signs and symptoms in himself. And because the team hadn’t packed cold-weather gear for the mission, he had nothing to keep him warm — not even a sleeping bag.

“I knew we were going to die, and it was from that course I knew all three of us will be dead by 6 o’clock that evening,” Ryan said. “All the different elements are at play: The wind chill and our wet clothing caused our body heat to drop at a certain rate.”

The three men continued to walk, zigzagging through the desert in single file until one of them, Sgt. Vincent David Phillips, could no longer keep pace. By that point, Phillips had discarded his weapon because his freezing hands couldn’t carry it any longer. As Phillips fell farther and farther behind, Ryan and his other teammate, whom Ryan refers to simply as “Stan” in his memoir, made the difficult decision to keep going. Phillips ultimately succumbed to hypothermia and died in the desert.

About midday on Jan. 26, Ryan and Stan looked across a little valley and saw a lone Iraqi man sitting on a rock. Stan told Ryan he’d join the man in hopes of reaching a vehicle. Stan did reach a vehicle, but he was captured by Iraqi soldiers and never returned. Now completely alone and still behind enemy lines, Ryan pressed on, equipped with nothing to navigate his way except some outdated maps from World War II and a janky compass. As day turned to night, he had to rely on the moon’s ambient light and constellations to stay on course.

Eventually he came to the banks of the Euphrates River. He passed by houses and barking dogs. Ryan didn’t know it at the time, but 1,600 Iraqi soldiers, as well as the entire local population, had been dispatched to look for coalition soldiers on the run. For the next three days and nights, Ryan followed the course of the river, hiding on ridgelines and inside tunnels and culverts in the daytime and walking at night, until he reached what he believed was the Iraqi border town of Krabilah. But it turned out that Syria was still miles away. He had no choice but to keep going.

“I was walking, I was collapsing, and then, finally, I collapsed and fallen against a wall and broke my nose,” Ryan told Coffee or Die. “My soles were falling off. I had blisters on my feet, and all my toenails and fingernails had fallen off. I hadn’t had water in three days, and I had maybe 12 to 24 hours before I died.”

On the morning of Jan. 31, Ryan saw a small building in the distance, and at that moment, he made a decision: If he was still in Iraq, he’d kill for food and water. But when he got to the building, he was greeted by a young man who gave him tea and water. Then, the Syrian secret police arrived, and for the next several hours Ryan underwent a brutal interrogation that culminated in a mock execution. Ultimately, however, the authorities decided to let Ryan go, and he was driven to the British embassy. Thus the nightmare finally ended.

As for the other seven members of Bravo Two Zero, one was killed in action; two, including Phillips, perished of hypothermia; and the other four were captured and detained at a prison in Baghdad, where they endured weeks of torture before finally being released at the end of the war.

Although Ryan had survived eight days and seven nights on the run, dodging bullets and Iraqi soldiers, he said it was the elements that came closest to killing him. He had bullets to fight off his enemies, maps and a compass to guide him through the desert, but without the proper cold-weather gear, he could only rely on his training to survive the weather. Looking back 31 years later, he sees that the difference between death and survival can boil down to survival instincts and intuition.

“After the conflict, I reflected on it,” Ryan said, “never thinking when I was doing this course, as a guide, being taught everything, all the signs and symptoms, everything that I would ever experience on an operation. I learned some very valuable lessons.”

Read Next:

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.