The Taney docked in Baltimore, 2011. Photo by Joe Ravi, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Cutter 37: The Last Ship Standing

How an aging Coast Guard cutter endured Japanese kamikazes, Nazi submarines, hurricanes, and more to become Pearl Harbor’s sole survivor

Her crew was running on two hours of sleep after three straight days of sustained combat when the alarm sounded. “General quarters, General quarters. All hands man your battle stations!” The command echoed throughout the cramped corridors of the 327-foot Coast Guard cutter Roger B. Taney as the 280 men on board scrambled back to their battle stations, knowing full well the enemy was now resorting to suicidal tactics.

It was May 1945, and kamikaze attacks plagued the fleet of American warships anchored off the coast of Okinawa. So far, the steam-powered Taney was holding her own, but the frequency of the suicidal attacks was increasing by the minute.

Taney off the coast of Okinawa, 1945. Note the battle-worn state of her hull. Photo courtesy of Ryan Szimanski.

She wasted no time destroying a Japanese bomber and assisting in downing numerous Japanese planes. Then, a lone kamikaze was spotted off the bow, bearing down on the nearby SS Brown Victory — a merchant ship loaded with essential supplies for the soldiers and Marines who were fighting ashore in what would amount to be one of the deadliest campaigns of World War II.

As the Japanese plane began its unrecoverable dive for the supply ship, Taney’s crew took aim with all of her available deck guns and opened fire. The tremendous wall of lead coming from the small ship hit the kamikaze, sending it crashing into the sea. It was the seventh enemy plane the Coast Guard cutter sent to the depths since arriving in theater a month earlier.

The USS Enterprise the moment a kamikaze flew into her flight deck, May 14, 1945. US Navy photo, courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command.

To this day, Okinawa remains the costliest battle ever fought by the United States Navy. Taney was one of the lucky few that survived the more than 1,900 kamikaze planes unleashed on the American fleet over the course of the 82-day engagement. By the time it was over, she had successfully repelled 250 attacks, saving her from joining the 36 American ships that were sunk and the 368 others that were damaged by the Japanese.

Designed with the Coast Guard’s primary mission of search-and-rescue in mind, Taney proved to be, as the executive director of the Historic Naval Ships Association Ryan Szimanski put it in an interview with Coffee or Die, “one of the most versatile ships of all time.” In addition to being the most heavily armed cutter in Coast Guard history, Taney was among just a handful of ships that fought in both the Pacific and Atlantic oceans during WWII. Later, she went on to serve in both Korea and Vietnam. In peacetime, she was used as a drug interdiction vessel, a deep-sea weather station, and, finally, a floating museum. In short, Taney has done it all, and she did it on outdated steam-powered technology.

Taney moored alongside Pier 5 in Baltimore. Photo by Mac Caltrider/Coffee or Die.

Today, the legendary ship, known officially as United States Coast Guard Cutter 37, resides in the still waters of Baltimore’s Inner Harbor. Anchored next to the Pratt Street power plant and towering high above the waterline, her main deck and its prominent anti-aircraft gun cut an imposing figure against the old brick buildings.

Every day, tourists pass her on their way to the National Aquarium. Those who notice her may stop to marvel at her silhouette, as if she’s just another example of the city’s beautiful, aging architecture. Patches of rust have started to sprout like liver spots on her once-pristine decks, and a small gift shop sells mugs and hats out of what was used to be her first-class berthing. It’s been 80 years since she was fighting back waves of enemy aircraft along foreign coastlines, and now Taney bears the solemn distinction of being the last surviving vessel of Pearl Harbor.

Steel plates conceal most of Taney’s wooden deck. Her sides still sport a coat of brilliant white paint that’s doing its best to shield the 86-year-old hull from the harbor’s notoriously dirty water. Painted on the side of the bridge are marijuana leaves and silhouettes of several planes. The leaves represent major drug busts carried out by Taney in the Caribbean; the planes are tally marks for some of the enemy aircraft the Taney downed during her days at war. Next to them is an impressive stack of ribbons and medals, arranged the same way they would be on a uniform.

Signs of the ship's age are beginning to show. Photo by Mac Caltrider/Coffee or Die Magazine.

Looking up at the array of colored stripes and airplanes 40 feet above the water’s surface, it’s easy to imagine the ship’s awards pinned on the puffed-out chest of a Coastie. For anyone walking or sailing past who can decipher the rainbow of awards, the display reveals just how much the old steam ship accomplished in her 50 years of service. Though, of course, unlike the men who crewed her during war and in peace, Taney has no voice. If her weathered deck could speak, it might spin a yarn about seamen sharing a meal after months of hunting Japanese submarines off Pearl Harbor. Or maybe her sleeping quarters might recall when anxious mariners tried to get some rest knowing Nazi submarines lurked just beyond the few inches of steel bulkhead separating their pillows from the dark abyss of the Atlantic. She might describe harrowing voyages across rough seas, or the 100 mph winds of Caribbean hurricanes, or the drug smugglers and enemy prisoners who were once locked in her bowels.

Ribbons and pictures tell an impressive story most passersby are unaware of. Photo by Mac Caltrider/Coffee or Die Magazine.

When her keel was laid in the Philadelphia shipyard in 1936, Taney’s engine ran on cutting-edge technology: two massive boilers, nicknamed “Huff” and “Puff,” which burned thick, brown fuel resembling chocolate pudding. Huff and Puff could generate enough steam to have her cutting through waves at 20 knots. She set sail for the Panama Canal in December 1936, steaming all the way to Hawaii. She helped supply the newly annexed Line Islands and also conducted her primary duty as a search-and-rescue vessel. Then, in 1939, with the prospect of war looming higher, she was outfitted for anti-submarine duty. Her Grumman JF-2 floatplane was replaced with depth-charge racks and her teeth were further sharpened with dual-purpose guns, anti-aircraft guns, and machine guns. Freshly painted with wartime-gray, Taney then steamed for Pearl Harbor.

On the morning of Dec. 7, 1941, when the Empire of Japan launched a surprise air attack on the United States, Taney was moored alongside a power plant, not unlike it is now in its current residence. Hawaii’s Pier 6 power plant in Honolulu Harbor was just seven miles from Pearl Harbor’s Battleship Row — the epicenter of the attack. To the Japanese pilots flying at 1,500 feet, Taney would have appeared just inches from the raid’s bull’s-eye.

USS William D. Porter sinks after she was near-missed by a "Kamikaze" suicide aircraft off Okinawa, June 10, 1945. USS LCS-86 is alongside, taking off her crew. Though not actually hit by the enemy plane, USS Porter received fatal underwater damage from the nearby explosion. US Navy photo courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command.

“All I could feel at the time was anger,” recalled Boatswain’s Mate 2nd Class Donald Brown to the Navy Times in 1986. “I was ready to pipe the morning colors when I saw what appeared to be an explosion on Sand Island. I was told to sound general quarters. We didn’t have a public address system, so I had to go all through the ship — fore and aft — yelling for the crew to man their battle station.”

The 7th was a Sunday, and much of Taney’s crew were still recovering from Saturday’s festivities. Some of the men and officers were still sobering up when the call to general quarters went out, but the entire crew, save for a single officer, was back aboard within four minutes. The ship’s gunners tried to engage the first wave from Pier 6, but the high-altitude Japanese Kate bombers were too high to hit. The 124 men aboard continued to fight throughout the morning, engaging every enemy sortie within range. When the second wave of aircraft flew over Pearl Harbor, Taney was eager to welcome them. Just before noon, a formation of five Japanese planes entered the mouth of Honolulu Harbor and beared down on Taney for a strafing run. Every gun on her deck opened up on the formation.

Once the most heavily armed Coast Guard cutter, Taney only has one remaining deck gun. Photo by Mac Caltrider/Coffee or Die.

“John Peterson, who was a gunner’s mate, manned his station on a .50-caliber [anti-aircraft] gun. I could hear that gun going off above me, and it was shortly after that that I saw a hole in the side of the Japanese plane’s big red dot,” Seaman Ken Maracek told the Navy Times. “I didn’t see it crash, but I know it was smoking. Taney got it.”

As soon as the attack finally ended, Taney began patrolling the harbor for Japanese submarines. In the week that followed, she carried out seven depth-charge attacks against enemy vessels.

“She spent 87 out of the next 90 days underway conducting those anti-submarine patrols,” Szimanski told Coffee or Die. “Going straight from fighting aircraft to the completely different mission of hunting submarines is so typical of Taney.”

Soogie was smuggled aboard in 1937 and became the ship's mascot for 11 years. She eventually retired and lived the remainder of her life in California. The terrier even had her own identification card. Photo courtesy of Ryan Szimanski.

After the US officially entered World War II, Taney became the only ship of the Coast Guard’s seven Senator Class Cutters to be deployed against the Japanese rather than the Germans, earning her the moniker “Queen of the Pacific.” Then, in 1943, after two years at war, Taney was called upon to help escort Allied convoys sailing for Europe across the U-boat-infested Atlantic.

On April 20, 1944, Taney — now the only cutter to ever be armed with the same weapons as a Navy destroyer — was elected as the flagship for an 85-ship convoy to the Mediterranean. En route, the convoy was attacked by a force of German Junkers JU-88s and Heinkel He 111 medium bombers. Under the cover of darkness, the German aircraft scored direct hits on five ships, sinking the destroyer USS Lansdale and the troop carrier SS Paul Hamilton. The latter exploded when ammunition stores were struck by a torpedo, killing all 580 men on board, most of whom were American soldiers bound for the Allied invasion of Normandy.

The ship's engine room remains ready. Photo by Mac Caltrider/Coffee or Die.

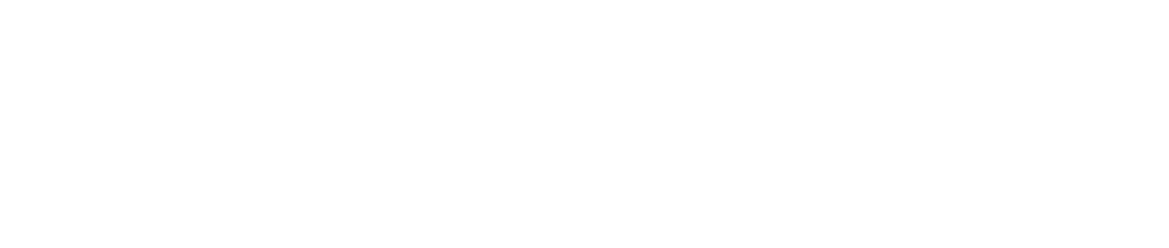

When the Allies finally triumphed in 1945, Taney reverted back to her primary mission as a search-and-rescue ship, and deployed to the Sea of Japan for service during the Korean War. Some years later, when the United States military became active in Southeast Asia, Taney’s role was changed yet again, this time as a provider of fire support for troops on the ground. She fired an estimated 3,400 rounds over the course of the Vietnam War. Additionally, her crew stopped and searched more than 1,000 vessels and also provided medical aid for thousands of Vietnamese civilians.

Patrick Aquia, a Coast Guard veteran whose first duty station was aboard Taney, told Coffee or Die that the ship’s humanitarian missions highlight the Coast Guard’s priority of preserving life rather than taking it.

“Anytime they anchored, our corpsmen and medical officers would be in the small boat headed to shore to treat people,” Aquia said. “We couldn’t keep them on the ship, but I’m proud of that. It’s the Coast Guard way.”

Taney's medical officer, Dr. Stephen Bartok, examines a Vietnamese child. Photo on display aboard USCGC 37.

Taney’s crew proved the old ship could fight during World War II, Korea, and Vietnam, but she proved just as useful in peacetime. By the ’80s, ships that ran on steam-powered boilers were being replaced by vessels with more sophisticated technology, yet Taney continued to serve in various capacities. She served as an offshore weather station, a drug enforcement vessel, and as a search-and-rescue ship, regularly saving Haitian and Cuban immigrants lost at sea. For many of her crew, being assigned to such an outdated ship was a blessing in disguise.

“I loved it. When I got told that I was going to one of the oldest vessels in the Coast Guard, I thought about the people who came before me that did giant things in life,” said former Seaman Jim McMurry. “Having my first ship be the Taney was a life-changer. It formed how I viewed the Coast Guard and the service's history.”

Inert shells fill the ammunition racks where deadly 5-inch, .38-caliber projectiles were once stowed. Photo by Mac Caltrider/Coffee or Die.

The Taney had some endearing quirks. For instance, the outdated boiler room — where old fuel, which McMurry described as “the thickest, goopiest, raw-sewage-smelling C-grade diesel you’ve ever seen,” was burned to make enough steam to power Taney’s engine — would get so hot that the Coasties who worked in there typically did so in their underwear. As the thinking went, if you could learn how to keep boilers like Huff and Puff running on “Navy sea slug,” you’d be prepared to keep any ship running.

“Every skill I ever learned on Taney, I used later in life,” Aquia said. “And the bonds we made were so strong, I mean we were tight. We worked hard and we played hard, and I think a lot of that came from the ship.”

The unique Coca-Cola paint job allowed Taney's crew to easily find the ladder in case the ship lost power. The ladder leads from the engine room to the weather deck. Photo by Mac Caltrider/Coffee or Die.

Indeed, at just 327 feet from bow to stern, Taney is not a particularly spacious vessel. Her boiler and engine rooms are a tangle of pipes, wheels, and gauges. Her passageways are a winding maze of steel and brass, interrupted by steep stairwells leading to more decks and more twists and turns. But those close quarters bred even closer bonds among her crew, and her sleek design left the Secretary class cutters better suited for rough seas than their longer, more advanced replacements.

“Taney was just like a Cadillac,” said Aquia. “She could take the waves and just roll with the punches. The newer ships rode waves like beer cans.”

Thirty-seven years after retiring, coffee cups still hang from their hooks near the bridge. Photo by Mac Caltrider/Coffee or Die.

Part of the reason Taney withstood rough seas better than most ships her size was the fact that her decks were still rounded in the style of old sailing ships, an intentional design known as camber. Thanks to her cambered decks — or “Humphrey Humps,” as the crew called them — Taney could not only shed any water she took on, she was also exceptionally suited to withstand large waves. After Taney and her Secretary class sister ships were no longer being built with such shapely curves, Taney’s last captain, Commander Winston G. Churchill, declared their kind “the most admired and most beloved Coast Guard ships ever.”

In 1986, Taney was officially scheduled for retirement. Taney’s final crew knew she would soon become a museum ship, yet they treated her no differently than before. No one stripped her for souvenirs. The expensive brass molding that once contained her ammunition stores was left alone and the prized helm remained in the wheelhouse. If anything, the final crew doubled down on their efforts to take care of her. There was a self-induced pressure to see Taney off in a condition that would have made all her former crew members proud.

The racks remain made just as the ship's final crew left them. Photo by Mac Caltrider/Coffee or Die.

Upon retirement, the ship was given to the Historic Ships of Baltimore Museum, a maritime museum that maintains several other important vessels from American history, including the USS Constellation (one of the original six frigates of the US Navy) and the submarine USS Torsk (credited with sinking the last enemy warship in WWII). According to Brian Auer, the museum’s executive director of operations, Taney no longer leaves the harbor, as the last of her saltwater intake valves were sealed in 2020. If left open, the sea would slowly eat away at her insides. Five museum ships have sunk so far this year, so Auer is doing all he can to ensure Taney doesn’t meet the same fate.

In 2020, the ship’s original namesake, Roger B. Taney (the notorious chief justice behind the Dred Scott decision to uphold slavery and deny African Americans citizenship), was quietly removed from her hull. The decision came following the murder of George Floyd by a police officer in Minneapolis, an event that galvanized a national anti-racism movement and inspired Baltimore residents to tear down local statues of Christopher Columbus. The speed at which residents succeeded in razing the monument prompted concerns that Taney may be targeted next.

Taney is now one of Baltimore Harbor's most notable features. Photo by Mac Caltrider/Coffee or Die.

Yet, despite the removal of her name, most of the ship’s former crew still call her Taney. To them, she has nothing to do with the former chief justice or the city’s history of racial inequality. To them, she remains a time capsule of a bygone era of sea service. She’s a footlocker of memories that generations of sailors made traveling the world’s oceans.

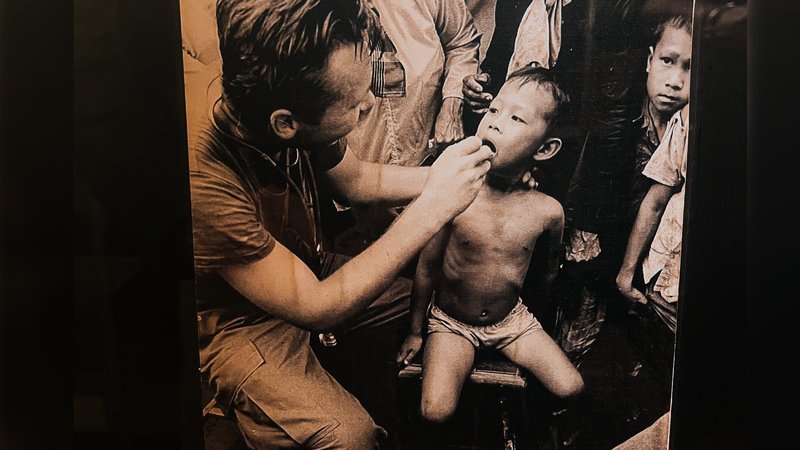

Calendar page marking Taney's last day of service. Photo by Mac Caltrider/Coffee or Die.

Today, not a single object appears out of place. Coffee-stained mugs still dangle from their hooks in the radar room and heaps of flags lay scattered about in the signals room. Racks remain stacked three high and neatly made with the same blue wool blankets that have always covered them. Metal trays are piled in the galley, ready for another meal.

The logbook still sits near the nightwatchman's chair, not encased in glass or even resting behind a roped-off area. It simply remains. The last entry rests next to a torn-out page of the ship’s calendar, dated Dec. 7, 1986. On it, a nameless Coast Guardsman scribbled a final message: “We're gone!”

Read Next: The Most American Moment of Pearl Harbor: Sailor Took On Japanese in Full Football Pads

Mac Caltrider is a senior staff writer for Coffee or Die Magazine. He served in the US Marine Corps and is a former police officer. Caltrider earned his bachelor’s degree in history and now reads anything he can get his hands on. He is also the creator of Pipes & Pages, a site intended to increase readership among enlisted troops. Caltrider spends most of his time reading, writing, and waging a one-man war against premature hair loss.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.