Courage 53: The 10th Mountain Division’s Forgotten Rescue Mission in Mogadishu

A week before the infamous Battle of Mogadishu — captured in the book and movie Black Hawk Down — a single Black Hawk was shot down over the Somalian city. Retrieving the helicopter fell to a team of men from the 10th Mountain Division. Composite by Coffee or Die Magazine.

Brett Archibald has spent the last 28 years haunted by the belief that he let his fellow soldiers down.

He didn’t.

Archibald was gravely wounded while laying down cover fire for his fellow soldiers from his HMMWV-mounted M60 in Mogadishu, Somalia. Before he was hit, his fellow soldiers from the 10th Mountain Division said, Archibald, then 26, had fought courageously to rescue the crew of a downed helicopter.

But after he was evacuated, the battle was so quickly forgotten — and even within the Army, remains so — that nobody ever bothered to tell him: The mission was a success, and you did your duty.

“We don’t leave a man behind, and at the point [when] I was shot, I thought we still had somebody to get,” Archibald told Coffee or Die Magazine. “I’ve had to live with that my whole life, even though that didn’t happen.”

Archibald was part of a Quick Reaction Force, or QRF, sent into Mogadishu after a Black Hawk helicopter — call sign Courage 53 — was shot down over the city not long after midnight on Sept. 25, 1993. The soldiers, part of the 10th Mountain Division’s Task Force 2-14, rushed to the crash site and spent hours defending it against local militiamen who bombarded the soldiers with rocket-propelled grenades and small-arms fire. Archibald provided suppressive fire from his HMMWV turret until he was shot through the thigh. His fellow soldiers dragged him away from the fight, though he didn’t want to leave. In his mind, the mission wasn’t over.

However, Courage 53’s two pilots had already made it back to base on their own while the Task Force 2-14 QRF was finishing the recovery of the bodies of the remaining crew from the crash. The patrol was preparing to return to base when Archibald was shot. Though three soldiers, including Archibald, were seriously hurt in the mission, none were killed.

But Archibald didn’t know any of that.

And though the battle to rescue Courage 53 isn’t widely known, it may sound familiar: A week after Archibald and his fellow soldiers rushed to Courage 53, the infamous and eerily similar Battle of Mogadishu occurred, immortalized in the book and movie Black Hawk Down. In that fight, many of the same 10th Mountain soldiers again convoyed into the city to find two more Black Hawks that were shot down, stranding their crews and dozens of Rangers and special operators.

Archibald missed that fight.

In the chaotic months after the larger battle — in which 19 Americans were killed — the battle to reach Courage 53 was almost completely forgotten, so much so that no one ever told Archibald it had been a success.

Also feeling forgotten was one of Archibald’s platoon mates, who lost the use of his legs in the rescue of Courage 53. He woke up in a hospital one morning months later with a Purple Heart sitting on his sheets — the closest thing to an award ceremony he ever received.

The men in Archibald’s squad received just one valor award for actions taken during the battle. And Archibald was later accused of being a liar when he wore his Purple Heart and Combat Infantryman Badge.

Even in the Army’s official after-action report of all combat in Somalia and other public documents about the Courage 53 crash or the Battle of Mogadishu, Archibald and his platoon are almost never mentioned.

For all intents and purposes, they were never there.

In 1993, the 10th Mountain Division pieced together a group of soldiers from three different units to deploy to Mogadishu. Most of the soldiers, including the senior officers, were from the division’s 2nd Battalion, 14th Infantry Regiment — hence “Task Force 2-14.” Archibald and 39 others from the division’s 1st Battalion, 87th Infantry Regiment, came along to augment. It was the early 1990s, and the chance for real-world combat was a rare thing. Leaders in the 87th hand-picked their 40 augmentees, including Archibald. A group from the 41st Engineer Battalion rounded out TF 2-14.

The task force would get air support from an aviation detachment of the 101st Airborne, which operated as Team Courage.

TF 2-14 arrived in Mogadishu in late July as part of Operation Continue Hope, a UN-sanctioned peacekeeping mission. The men from 1-87 were charged with patrolling supply routes in their 10 hardshell HMMWVs, and they also assisted with QRF.

Hostilities had been on the rise for months. Forces led by Somalian warlord Gen. Mohamed Farrah Aidid ambushed and killed 24 Pakistani soldiers in June 1993 and killed four US military policemen on patrol on Aug. 8, 1993. To respond to the deaths of Americans, a force of Rangers and other special operations troops dubbed Task Force Ranger touched down three weeks after TF 2-14 did.

One reason that the rescue of Courage 53 remains lost to history may be the very different missions of the two American task forces that shared the same city that September. The 10th Mountain troops were acting for the United Nations, whereas TF Ranger was there to pick a fight: capture Aidid and dissolve his organization.

According to the Army’s after-action report on operations in Somalia, TF Ranger conducted six raids in the weeks leading up to the events of Oct. 3. They didn’t find Aidid, and with each engagement, Aidid’s men grew more confident in taking on both TF Ranger elements and the less-offensive-minded TF 2-14 troops.

Olin Rossman, a 1-87 squad leader, remembers the attacks gradually escalating from occasional pop shots on patrol to full-blown ambushes and firefights. When he and his guys got into a four-hour shootout on Sept. 13, Rossman, then 26, thought it would be the peak of the action on their deployment.

Just over a week later, a Team Courage helicopter was on a late-night patrol over the city. Its call sign was Courage 53. The helicopter was about 100 feet in the air when a militia fighter on a roof fired an RPG that scored a direct hit. Three crew members were killed by the explosion, but the pilots managed to crash-land the stricken helicopter in the city. The chopper skidded to a stop in an intersection, breaking into two parts.

Like TF 2-14, Team Courage was in Somalia as part of the UN mission. And as a UN asset, it fell to TF 2-14 to respond.

“The first thing I remember is the first sergeant busting into my hooch going, “Get your ass up, we have a bird down,” Rossman told Coffee or Die.

Rossman quickly got dressed, assembled his team leaders, and briefed them on the little information he had at the time: Courage 53 was down in the city with possible survivors, and TF 2-14 had to go find them.

The squad loaded into two HMMWVs and followed the lead element of 2-14 vehicles as they sped off to the crash site under command of a captain from the 2-14, Michael Whetstone. After the lead vehicles missed a turn, Rossman and his men were the first to arrive at the scene.

Inside the still-smoldering wreck of Courage 53 were the remains of Pfc. Matthew Anderson, Sgt. Ferdinan Richardson, and Sgt. Eugene Williams. Both the pilot and co-pilot, Chief Warrant Officer 3 Dale Shrader and Chief Warrant Officer Perry Alliman, were missing.

What Rossman and the 2-14 convoy didn’t know was that Shrader and Alliman had escaped the wreck. Shrader had a broken arm, but Alliman’s injuries were such that he could move only with Shrader’s help as they took shelter in a nearby alley.

The burning airframe illuminated the faces of militia members descending on the crash site as Shrader and Alliman waited for help to arrive.

“I tried to radio out to contact someone,” Shrader later told his hometown newspaper, The Roanoke Times, “but each time it set off a loud beacon anyone in the area could hear. I turned it off.”

A Pakistani armored personnel carrier soon arrived near the crash site. But when a Pakistani soldier jumped out, he was immediately shot and the vehicle withdrew.

When the militiamen threw grenades at the pair, Shrader fired his pistol in return.

“One of them got brave and ran down the alley with his AK on automatic fire,” Alliman told Army Aviation Magazine in 2002. “He was shooting right over our heads, but Dale shot him when he got past us.”

With that, Shrader was out of bullets and the two could only flee.

“Dale came over at that point and tried to comfort me,” Alliman told the magazine. The pilot whispered a Bible verse. “Perry … John 3:16,” Shrader said.

Alliman later told an Army reporter that he eventually asked Shrader — a Bible study teacher at home — why he had cited the verse, but not actually recited it.

“I asked him years later, ‘Dale, why didn’t you just say the verse?’” Alliman recalled. “He said, ‘I was so scared, I couldn’t remember it.’”

As the two pilots waited, a man approached them and motioned to them, saying, “American boys, come.”

The man led them to another APC, this one from the United Arab Emirates, that arrived nearby.

“Perry and I believe he was an angel, to show us the way,” Shrader told The Roanoke Times.

Shrader was awarded the Silver Star for defending himself and his co-pilot for nearly two hours. Not long after the two men were rescued, QRF arrived to look for them.

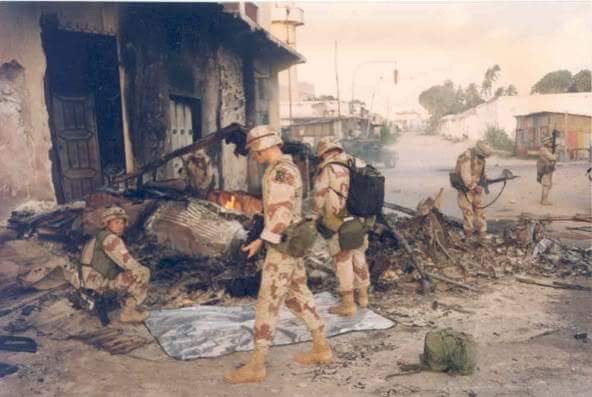

At the remains of Courage 53, the 1-87 troops established a perimeter. When the radio call came in confirming the pilots had been recovered, the sun was beginning to rise. As morning prayer blasted through a nearby loudspeaker, small crowds began to form in the streets, a mix of curious onlookers and armed fighters hiding among them.

The helicopter’s wreckage was burned nearly to ashes, with very little evidence of human remains. Whetstone, the QRF commander, found a set of dog tags by sifting through ash inside the burned hulk, he later wrote in a book about his time in Mogadishu. But the patrol had rolled out so quickly that no one had grabbed body bags to collect whatever remains could be found. Rossman was fetching a poncho to use when he noticed the crowds had dissipated. As soon as he completed the thought, an ambush erupted around him.

Bullets snapped as they zipped by and RPGs narrowly missed their mark all around him. The patrol responded with a barrage of its own, suppressing the enemy with everything it had. Knowing that his men were running low on ammo, Rossman used a lull in the fight to rush to the rear of the HMMWV to resupply the gunners.

Archibald was manning his M60 on the HMMWV when a nearby RPG blast knocked several soldiers to the ground, including 23-year-old Pfc. Rolando “Poncho” Carrizales. Rossman rushed to Carrizales and dragged him to safety behind the HMMWV. There was no blood at first, Rossman recalled, and then it was everywhere.

A 7.62 round had struck Carrizales in the neck and exited his back. Rossman piled one field dressing after another on Carrizales’ neck, but each quickly soaked through. The round had clipped the carotid artery, and no number of dressings would stop the bleeding.

While Rossman desperately worked to save Carrizales, Archibald kept up constant suppressive fire. He remembers swinging his weapon from right to left, engaging one target after another, when he felt his feet slipping on the turret stand. He looked down and saw his trousers drenched in blood from the groin down.

“I was pissed,” he said. “I went instantly to anger. I couldn’t believe I got shot.”

Sgt. Willie Boult pulled Archibald down from the turret, and Rossman jumped behind the gun. As the morning light grew, the fighting picked up and helicopter gunships began making passes, raining brass on the men as they tried to break contact below.

Archibald was patched up and rushed to a medical HMMWV. Medics first loaded up Archibald and then the critically hit Carrizales before the vehicle sped off. As rounds hit around the racing HMMWV, Archibald grabbed the medic’s M16. The truck was driving so fast that each time it rounded a corner, the rear doors swung open. Each time, Archibald fired a volley out the back.

When the rest of the patrol finally broke contact, two men were badly hurt: Archibald and Carrizales from Rossman’s squad. And on the return trip, just two blocks from safety, Sgt. Christopher Reid, a 2-14 soldier, was hit by an RPG. The explosion tore off his hand and part of one leg. Reid passed out during the frantic drive back to base and woke up five days later in Germany.

The battle and rescue of Courage 53 left Rossman rattled. Outside of the special operations community, the Army was almost entirely a peacetime force. And training can only prepare a person so much. Combat is messy, and things seldom go precisely as planned. And though Rossman knew all of that, it didn’t stop him from beating himself up.

“My thought process was ‘My two guys are wounded because of something I did wrong.’ Then the self-doubt came in. What could I have done better, faster, different, anything,” Rossman recalled. “It wasn’t that the enemy did it right; it was something I had done wrong.”

Back at their base, the platoon cleaned out the vehicles. They swept out the brass and mopped up the blood while engineers replaced the bullet-riddled windshields. Then it was back to work.

Carrizales was given a 50-50 chance of survival when he started his journey home. He slipped in and out of consciousness as he made his way from Somalia to Europe and then to the US, ultimately landing in a hospital bed at the Brooke Army Medical Center in his home city of San Antonio, Texas.

When Carrizales finally came to, he was unable to speak because a tube was running down his throat. He tried to look around the room, but he could only shift his eyes because a halo device protecting his neck restricted any upper-body movements. When he tried to wiggle his hands and feet, nothing happened. And though he would regain the use of his hands and arms later, he would never walk again.

During one of Carrizales’ early days in the hospital, a nurse walked into his room and mentioned that there was a Purple Heart on his chest. Carrizales looked up at the man, confused. The nurse held it up for him to see.

That was the Purple Heart ceremony for Pfc. Rolando “Poncho” Carrizales.

When Reid, the badly injured 2-14 soldier from the Courage 53 mission, returned to Fort Drum after several months in the hospital, the battalion held a “welcome home” formation for him. At the ceremony, according to a Washington Post article published that Christmas, was Army Chief of Staff Gen. Gordon Sullivan, whom Reid invited to his upcoming wedding.

Carrizales was medically retired in the spring of 1994, but even that process was remarkably lackluster. One day he was in, and the next day he was out, Carrizales said. When he got his paperwork for his discharge in the mail, he wondered whether it was official because he’d never signed anything.

Carrizales’ paperwork noted his Purple Heart; it even mentioned that the award was for wounds in Somalia. But a notation for his Combat Infantryman Badge, which is awarded for active engagement in ground combat, was missing: one more thing the Army got wrong on his way out.

“I didn’t get anything, no ceremonies, nothing,” Carrizales said. “I felt like I was pushed aside and taken to the rear with nothing, nobody coming to talk to me. It was an ugly feeling, especially being in the ICU unit; it [was] dark at times … Even when I got my DD214, there was nothing there. My heart just went to my stomach and I felt sick.”

As for Archibald, he reenlisted so he would get proper medical care for his wounds, and he was transferred to Fort Carson in Colorado. When he checked into his new unit in full dress uniform, he was called a liar for displaying his Purple Heart and Combat Infantryman Badge.

Just eight days after the crash of Courage 53, the men from 1-87 and much of the rest of TF 2-14 fought their way into and back out of the city again in the Battle of Mogadishu, rescuing more than 100 Rangers and special operations soldiers on Oct. 4, 1993.

For their actions taken over the course of the deployment, the platoon was told they could nominate a single soldier for a valor award, according to former platoon leader Brian Puckett.

The question of awards for Mogadishu sprang back into public view in September 2021 when the Army upgraded various awards given to 60 Rangers and other special operators to Silver Stars. That brought the total of Silver Stars given to TF Ranger personnel to at least 90.

Troops from the 10th Mountain received just four Silver Stars in the months after the battle. Additionally, TF 2-14 soldiers received 12 Bronze Stars with a “V” for valor and 12 Army Commendation Medals. One of those Bronze Stars was upgraded to Silver this year as part of the TF Ranger upgrades.

The 1-87 troops fared even worse. Puckett, the platoon leader, recommended a Bronze Star for Spc. Arthur Houston, who exposed himself to enemy fire to drag a wounded comrade to safety and provided suppressive fire while his team treated the soldier in the larger Black Hawk Down fight. That award was ultimately downgraded to an Army Commendation Medal with a “V.” The rest of the men, many of whom fought on both the Courage 53 and Black Hawk Down missions, received Army Achievement medals — noncombat awards for fairly routine professional achievements.

One of 2-14’s Silver Star recipients was Whetstone, the 2-14 ground commander of the Courage 53 QRF mission. At 35, Whetstone was nearly twice as old as his youngest privates. He’d enlisted in the Marines at 25 before becoming an infantry officer in the Army. In an interview with Coffee or Die, Whetstone said he hadn’t known the men of 1-87 personally in Mogadishu, but he was well aware that they were in the fight, standing shoulder to shoulder with his own men throughout the deployment. Until recently, he said, he was unaware that their service and sacrifices had gone unnoticed.

“After all these years, to find out that soldiers who had been fighting with us got no recognition is just a miscarriage of justice,” Whetstone said. “We owe them their due recognition.”

Editor’s note: This article has been updated to reflect that the official name of the award given by the US Army for active engagement in ground combat is the Combat Infantryman Badge.

Read Next:

Dustin Jones is a former senior staff writer for Coffee or Die Magazine covering military and intelligence news. Jones served four years in the Marine Corps with tours to Iraq and Afghanistan. He studied journalism at the University of Colorado and Columbia University. He has worked as a reporter in Southwest Montana and at NPR. A New Hampshire native, Dustin currently resides in Southern California.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.