‘God Left Me Alive To Do This’: FDNY Veteran Tim Brown Recalls the Heroism and Horror of 9/11

A lone fire engine at the crime scene in Manhattan where the World Trade Center collapsed following the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attack. Surrounding buildings were heavily damaged by the debris and massive force of the falling twin towers. Photo by Chief Photographer’s Mate Eric J. TIlford, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Sept. 11, 2001, was a beautiful Tuesday morning. Blue skies, no humidity. The kind of morning pilots call “severe clear.” Tim Brown was a 17-year veteran of the New York City Fire Department on that fateful day when he and hundreds of other first responders worked to rescue people from unfolding chaos and destruction. As many Americans watched the horrifying scene play out on their television screens, Brown and a group of paramedics were within 20 feet of the south tower when it began to collapse.

“It was so loud and so immediately obvious what was happening,” Brown says.

The collapsing floors forced air down and out of the tower with so much force that wind speeds at street level surpassed those of category-five hurricanes.

“One piece of steel cracked, and it reverberated through lower Manhattan,” Brown says. “I turned around and told the paramedics to follow me.”

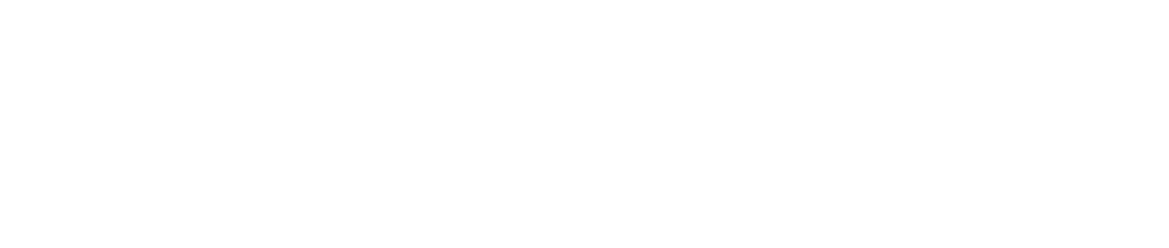

Brown was taught that, when a building collapses, you can’t outrun it. Your best chance of survival is to get next to a strong vertical column, such as a support beam. At the entrance of the Marriott hotel — specifically, the Tall Ships Bar & Grill — was a vertical steel beam, strong enough to support the 22-story building.

“In the snap of a finger, everything went pitch black,” Brown recalls.

The collapse created a surge of smoke and debris that snuffed out all light and breathable air. Dust instantly filled Brown’s ears, nose, eyes, and mouth. His legs lifted off the ground, parallel to the floor from the 185 mph rush of air. The noise was so loud Brown could only compare it to sitting on a stool in the middle of the tarmac at JFK International Airport, surrounded by 747s with their engines at full-throttle. It took nine seconds for 110 floors of concrete, steel, and people to collapse around him.

Twenty years later, Brown is alive to tell the tale, and he says his life’s purpose now is to tell the stories of the hundreds of brave first responders and ordinary citizens who perished while helping others on 9/11.

“I got out. I lived. I’m here to be the voice of those heroes,” Brown tells Coffee or Die Magazine. He says not a day passes in which he doesn’t think about the friends he lost.

Tim Brown started out as a new firefighter in Hunts Point in the South Bronx, a formidable place to learn the ropes in the late 1980s, but a place where he learned a lot of wanted and unwanted valuable lessons. From there, Brown moved to Ladder 4 in Times Square before moving back to the Bronx as part of Special Operations Rescue 3. Following nearly a decade at the pinnacle of the FDNY, Brown traded in his burned and charred turnout gear — a source of pride for salty Bronx firefighters — for a green helmet, becoming part of Mayor Rudy Giuliani’s newly created Office of Emergency Management.

Brown started the morning of 9/11 as he did any other workday. He was enjoying breakfast in the third-floor cafeteria of 7 World Trade Center when the power went out at 8:46 a.m. As a veteran firefighter, Brown knew only something significant could cause a modern high-rise building to lose power, but when the power came back on five seconds later, he wasn’t worried. It wasn’t until people started running away from the windows that Brown knew there was a bigger problem.

“I had to grab one lady by the shoulders and shake her back to reality to ask what happened,” Brown says. “She told me a plane hit the tower, and that was the first I knew of it.”

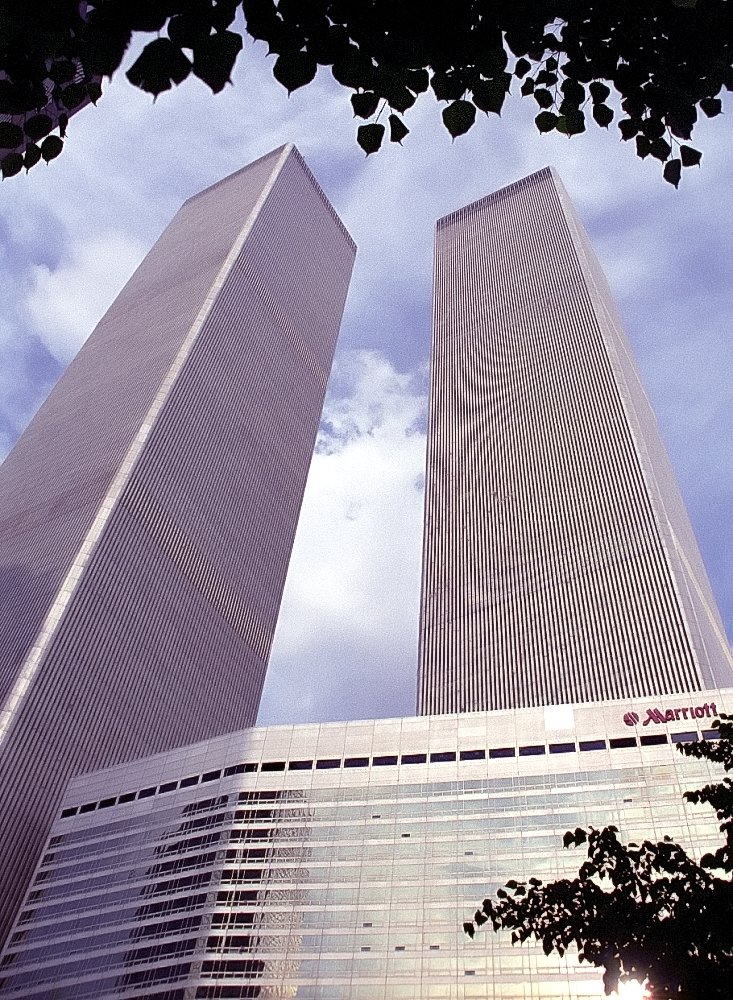

Brown rushed to the 23rd floor Watch Command to ensure it was doing a full activation: calling every federal, state, and local resource to respond to ground zero. Responding to an airplane striking one of the Twin Towers would require the coordination of hundreds of first responders. Realizing he was no help on the 23rd floor of 7 World Trade Center, Brown ran back to his car, shed his tie, and grabbed a radio. To do so, Brown had to climb the outdoor staircase leading to the World Trade Center plaza. The route would later become known as the “survivors’ stairs” for the hundreds of people who managed to survive that day by escaping down those stairs. But while crowds fled down the stairs for their lives, Brown was climbing up. He was climbing toward the epicenter of the chaos.

“I looked out over the plaza, and it was littered with debris, smoke,” Brown remembers. “There were sheets of paper floating down everywhere. That’s when I realized this was something much bigger than a Cessna.”

Brown moved through the falling debris to the lobby of the north tower, where a makeshift command post was being established. As he approached an escalator feeding into the lobby, something struck him. Everywhere he looked, people were helping one another. Not firefighters or police, but ordinary office workers.

“Instead of people doing what you might expect, like pushing and trampling, they were doing the opposite,” Brown says, recalling the moment. “For every elderly, obese, or injured person, there were four or five office workers helping them. I remember thinking to myself, no matter what happens today, we are going to be just fine, because that is the true human spirit in all of us. When someone trips, we instinctively reach to pick them back up.”

Once inside the lobby, Brown laughed to himself. Spanning the entire lobby were firefighters in their yellow and black striped coats, and he finally understood why cops called firefighters “bumblebees.” Brown waded into the swarm of firefighters awaiting orders to go up into the north tower and bumped into the back of a bumblebee. The man turned around, and Brown recognized him as firefighter Chris Blackwell.

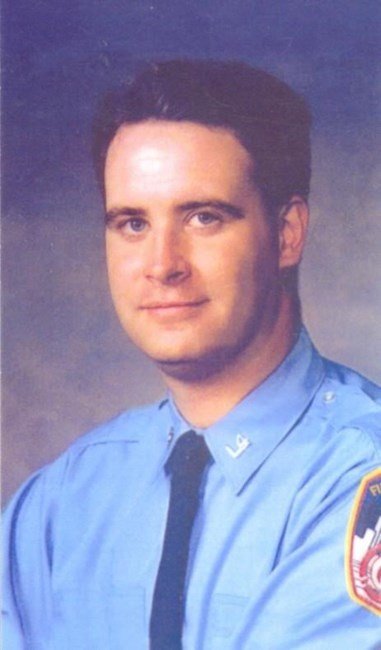

Blackwell worked on the same shift Brown did for years.

“Chris was a brother to me,” Brown says. “We were Bronx guys. The Manhattan guys always had their ties on and were clean-shaven; all their gear was in order and worn properly. But Chris and I were Bronx guys, so all our gear was burned and melted. The helmet never sat on your head right because it was burned up so bad, and we never really shaved as much as we should have. That’s who we were.”

In his time off, Blackwell volunteered as a paramedic. He dedicated every moment of his life to helping people, and he was good at it.

“Anytime we had someone who was seriously injured, we tried to get them into Chris’s hands because we knew that was their best chance at surviving,” Brown said.

Blackwell wasn’t just a hardcore, special operations firefighter from the South Bronx, though. He was also the guy who lived to make people laugh. Anytime Brown and Blackwell crossed paths at a fire, they performed the same odd greeting ritual. They would stand inches apart from each other at the position of attention, Blackwell would reach up and remove his ever-present stub of an unlit cigar, and the two badasses would briefly kiss on the lips. They did this every time, without exception. Smoke and snot from fighting fire never got in the way of a chance to make the rest of the men laugh.

On Sept. 11, 2001, in the lobby of the burning north tower, Brown and Blackwell performed the same ritual before acknowledging the seriousness of the situation.

“Timmy, this is really bad,” Blackwell told Brown. “Be careful.” Before Brown had a chance to discuss the situation further, his friend turned and headed up the stairwell of the north tower. He never came back down.

Brown didn’t have time to dwell on the goodbye. He heard someone shout his name from across the lobby, and he turned to see another familiar face: Capt. Terry Hatton.

Hatton was the 6-foot-4-inch captain of Manhattan’s elite special operations Rescue 1 and Brown’s best friend. He was a firefighter who was always squared away, with a pristine helmet, spotless gear, and never a smudge on his face. He was the poster child for the FDNY. With a uniform awash in medals, there were never any doubts about Hatton’s bravery in the face of fire, but he held the respect of the entire department for his intelligence.

“He was always six, seven, eight steps ahead in his plan. That’s why he was the captain of Rescue 1,” Brown said.

Brown ran to Hatton, who was waiting with open arms. He held a Halligan tool in one hand and a flashlight in the other. Brown nearly disappeared in the bear hug from the tall captain. As the two veteran firefighters embraced, Hatton put his mouth next to Brown’s ear and whispered, “I love you brother. I may never see you again.”

Brown blew him off. The two had been through so many death-defying situations before: Bad fires, bombings, building collapses — they’d been through it all. Brown assumed they’d get through this one too. After the ominous words, Hatton turned, rallied the men of Rescue 1, and went up the stairwell. Hatton was able to lead his crew all the way to the 83rd floor, where they began fighting the fire being fed by the plane’s 20,000 gallons of jet fuel, but a localized collapse trapped the firefighters. The last words anyone heard from Hatton came over the radio, “Mayday! Mayday! Mayday! Rescue 1 is trapped.”

Any time a mayday call was sent over the radio, people turned to Rescue 1 for help. Now it was FDNY’s most elite unit that was calling for help.

Before Brown was aware that Hatton was trapped, more firefighters rushed into the lobby with the news that a second plane had just hit the south tower. A quick meeting of the department’s leadership determined how to best divide their forces. New York was now dealing with the two worst disasters in the city’s history taking place right next to each other. Brown and Assistant Chief Donald Burns decided they would move to the south tower and establish a second command post.

If you looked up “Irish Fire Chief” in the dictionary, you’d see a picture of Donald Burns. With red rosy cheeks and lines of hard-earned wisdom carved into his face, Burns looked like a caricature of a seasoned FDNY chief. He was a 39-year veteran of the department and a walking encyclopedia of New York’s streets and buildings.

After dodging falling debris from both towers, they eventually made it inside the lobby of the south tower, where Burns gave his last command to Brown.

“I’ve ordered the fifth alarm,” Burns said through the corner of his mouth in his thick New York accent. “Those additional 350 firefighters are headed to the north tower first; we’ll have to wait for our guys. Do your best, and be careful. We’re at war.”

Leaving Brown no time to dwell on the gravity of those words, a woman approached him, yelling that there were people trapped in an elevator. Burns told Brown to leave the command post and go help.

The hoist doors were open, exposing the elevator shaft. The car had not come down all the way, and only about 5 inches of the elevator were exposed at the top, revealing the feet of everyone trapped inside. The men inside were trying to pull the car free and create enough room for people to get out, but the elevator was immovable. The car’s cables had been severed by the plane, and the car had free fallen 70 floors to the lobby. Its emergency brakes engaged in time to prevent it from slamming into the ground, but they had locked the car in place. It would require heavy machinery to free the passengers. Below the elevator, at the bottom of the shaft, jet fuel had pooled. The fuel was now on fire, turning the elevator into a human frying pan.

“So here I am, standing inches from these people in my useless Mayor’s Office jacket, unable to help,” Brown recalls. “What they needed was a real firefighter.”

He turned around in desperation, looking for something that might be able to help, and spotted his longtime friend, firefighter Mike Lynch from Ladder 4.

“Timmy, I got it,” Lynch said to Brown as he walked up and put a comforting hand on Brown’s shoulder.

Those words conveyed that Lynch had the training, the equipment, and the intestinal fortitude to help those people trapped in the heating elevator. Before Brown and Lynch had time to talk, Brown’s radio screamed to life.

“Urgent, urgent, urgent! Third plane inbound. Seek immediate cover!”

Lynch chose to remain with the people trapped in the elevator while Brown ran for the command post. He found a working phone and told the operator to connect him with the White House. Busy signal. He then asked to be connected with the Pentagon.

“The Pentagon is also under attack,” came the voice on the other end.

It was then that Brown began to understand the scale of the terrorist attack. That’s when he noticed how crowded the lobby of the south tower was becoming. Hundreds of office workers, many burned or with broken bones, managed to make their way down the tower’s dark and smoky stairwells. Round and round they had climbed, some coming from as far as the 80th floor, until they finally opened the door of the lobby and were greeted by an army of first responders. Exhausted from their journey down to the lobby, many people collapsed upon seeing professionals there to help. But this was causing a problem of overcrowding. Recognizing the hazard, Brown left the lobby to wrangle more paramedics to come and help move the injured out.

As Brown began moving along Liberty Street, he looked toward the road and saw an image that burned itself into his brain forever. Just a moment before Brown had stepped outside, a firefighter had been crushed by someone leaping from the tower. The bodies had collided with such force that the two were now one. Brown looked on helplessly as other firefighters attempted to pull part of their dead comrade free of the conjoined corpses. The deceased man was the first firefighter to die on Sept. 11, 2001.

“Timmy!” a voice called, pulling Brown’s attention away from the dead firefighter. It was Lynch, lifting the “jaws of life” off of a firetruck. He planned to use the tool to force the gap in the elevator wide enough for people to squeeze through, but Lynch needed a hand carrying the cumbersome piece of equipment. Before Brown could get to him, another firefighter intercepted to help. Lynch and Brown exchanged waves, and Lynch moved back into the south tower.

Brown turned his attention back to the task at hand and located more paramedics along West Street. He told them they had to move toward ground zero. Normally, paramedics would establish a triage location at a safer distance, but there were simply too many people to move. Three paramedics threw helmets on, filled a stretcher with medical equipment, and followed Brown back toward the chaos in the south tower.

As they passed in front of 3 World Trade Center — then a Marriott hotel — they hugged the walls to avoid being hit by people jumping from the upper floors of the Twin Towers. Just as Brown and the paramedics got within 20 feet of the south tower, it started to collapse.

As suddenly as the nightmare scenario had started, it was over. With the south tower and 7 World Trade Center turned into rubble all around him, Brown was miraculously still alive. Once he accepted the impossibility that he was still conscious and breathing, escape became the only thing on his mind.

“I started going deeper into the lobby of the Marriott — or what used to be — and I came to a metal roll-down gate,” he remembers. “I put my fingers underneath and started lifting it up. I got about 2 inches up, and all these fingers came from the other side.”

Together, Brown and the strangers on the other side lifted the gate. On the other side were about a dozen people who had been trapped. The collapse had killed the majority of their group: a mix of firefighters and the civilians they had been rescuing. The survivors — all civilians — were standing on a cliff above a seven-story drop before Brown helped open the gate. The group turned back around and headed into what was left of 7 World Trade Center.

Despite it being a crystal-clear day in New York, no sunlight penetrated the cloud of dust and smoke that smothered ground zero. It was pitch black.

Through the darkness came a single light. A New York City firefighter was climbing over the rubble with a flashlight, calling out for survivors. Soon, the group of survivors Brown was leading formed a human chain, and together, they made their way to the light.

“I was still in fight or flight mode,” Brown recalls. “In my crazy head, I was thinking I would run to the Hudson, jump into the river, and swim to New Jersey.”

Before Brown made it to the river, he heard frantic calls for help come over his radio. The voice snapped him back into rescue mode, and he turned around and began making his way toward the West Side Highway. By the time he got to where the cries for help originated, other firefighters had already pulled the trapped man from the rubble and were treating him.

Once Brown linked up with more surviving firefighters and members of the Mayor’s Office of Emergency Management team, he started making his way north toward the location of the Mayor. At 10:28 a.m., Brown heard screams coming from behind him, and he turned in time to see the north tower collapse into another storm of smoke and debris.

“I knew many, many of my friends were in that building and that they were gone,” Brown says.

Brown turned back and kept running. The north tower’s dust cloud chased after him, and light debris pummeled the street around him. Somehow, Brown survived the second collapse, too.

“I’m here to be the voice of those heroes,” Brown says. “The 343 firefighters, 37 Port Authority police officers, and 23 New York City police officers, who all did what Chris Blackwell, Donald Burns, and Terry Hatten did. They all knew that, once they went into those stairwells, they likely would not be coming back. They all still did it.”

The horror of the attacks did not end on Sept. 11, 2001. The last survivor was pulled from the rubble 27 hours after the north tower collapsed. Recovery efforts lasted weeks, and ground zero did not begin to resemble anything normal for years afterward. As missing-person fliers covered New York City’s storefronts, one of the names was that of firefighter Mike Lynch. Brown told recovery personnel to search the area where the south tower’s elevator shaft had once been. Next to the destroyed shaft, they found Mike Lynch’s body. Beside him were the “jaws of life” and the bodies of those who never made it out of the locked elevator. Lynch had chosen to stay with them until the tower collapsed.

“I believe to this day that the reason God left me alive was to do this, to tell the story of all these hero firemen and police officers and the innocent human beings and the people that were helping each other,” Brown says. “That’s important to give people hope, you know? There was a lot of evil that day, but there was a lot of good, too.”

Twenty years after the terrorist attack, Brown continues to share these stories with anyone who will listen. He’s determined to remind as many Americans as he can that we can’t let the world forget what people like Mike Lynch and Terry Hatten did in the midst of certain death. For Brown, it’s that selfless spirit that makes the darkest of days bearable. It’s the lone firefighter, wading into the darkness with a single light, that fills him with hope for our nation’s future.

Read Next: ‘Able Danger’ — The Pentagon’s Plan To Suppress a 9/11 Controversy

Mac Caltrider is a senior staff writer for Coffee or Die Magazine. He served in the US Marine Corps and is a former police officer. Caltrider earned his bachelor’s degree in history and now reads anything he can get his hands on. He is also the creator of Pipes & Pages, a site intended to increase readership among enlisted troops. Caltrider spends most of his time reading, writing, and waging a one-man war against premature hair loss.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.