Coffee or Die Magazine embedded with US Border Patrol agents in the waning days of February 2022, from the wildlands of West Texas to the urban sprawl of Sunland Park, New Mexico. Composite by Coffee or Die Magazine.

LOBO, Texas — The 49-year-old lawman squinted at the top of what everyone here calls Marijuana Mountain, then glanced down at the furrows dragged across a dust trail by a US Border Patrol truck hours earlier just north of the ghost town of Lobo.

It was 3:28 p.m. on Feb. 23, 2022, in Culberson County, and to Station Patrol Agent in Charge Jose Aleman, something just wasn’t right about the canyon. A steer wouldn’t make that crimp in the tarbush. No whitetail would mat the tobosa like that.

For the past 17 hours he’d been hunting a group of Guatemalan stragglers that left Mexico, crossed the trickle of the Rio Grande about 20 miles southeast of here, and scaled the Sierra Vieja range, which includes Marijuana Mountain.

Compared with the other crags, it’s a gentle slope of scree and weeds, and drug mules like to descend it before cutting across the Lado Ranch, hiking north.

On Feb. 23, 2022, near the ghost town of Lobo, US Border Patrol Station Patrol Agent in Charge Jose Aleman tracks the faint traces of undocumented men walking through the West Texas brush. Photo by Justin Merriman for Coffee or Die Magazine.

Aleman’s agents caught most of the Central Americans, but no migrants were found here. Aleman snaked through the grass, eyeing the snapped sprigs of creosote, stretching his boots over an upturned rock, a splintered mesquite branch.

He was trying to decide if this was an overnight “layup” for a group of men toting burlap bags fat with pot or narcotics, or a few lost Guatemalans short on water.

It’s called sign cutting. Aleman was reading how the party’s sneaker treads “kicked off” in the grass or rubbed “Christmas trees” in the road dust. An experienced agent knows how to read the prints people leave on nature.

At 4:12 p.m. Aleman stopped by a wire fence.

There was a steady whistle of wind on his neck, the only sound in the draw. No bird calls. Just mountains, and scrub, and the silent and unrelenting scorch of a cold sun.

On Feb. 23, 2022, near the ghost town of Lobo, US Border Patrol Station Patrol Agent in Charge Jose Aleman tracks the faint traces of undocumented men walking through the West Texas brush. Photo by Justin Merriman for Coffee or Die Magazine.

The tracks were made in the last few hours, shortly after a US Border Patrol truck raked the roadway, Aleman announced.

They might’ve holed up in the grama and agave, watching the vehicle drive past, but they were tired. You could see that in the way they dragged their feet, he said. Three, maybe four men, carrying heavy packs. They probably wore carpet on the soles of their shoes to help whisk away their footsteps.

He pointed to where they went under the barbed wire and kept trekking east, toward what the agents call the Three Sisters, a trio of cones that rise angry from the desert in a black-brown shimmer. They’re the landmarks drug mules use to reach the Wylie Mountains.

There, Aleman said, the men will summit those ridges, which will put them near Interstate 10 east of Van Horn. Ten thousand vehicles motor by there every day. The mules will pray that one is waiting for them.

Aleman figured they had 20 more miles of hard hiking in front of them. Roughly two days. “So they’re catchable,” he told The Forward Observer, a special edition of Coffee or Die Magazine.

He said it all again to his agents on the other end of the radio, somewhere in the vast tract of rock, ranch, and sky.

On Feb. 23, 2022, near the Texas ghost town of Lobo, Station Patrol Agent in Charge Jose Aleman tells his US Border Patrol agents to be on the lookout for a group of undocumented men walking through the brush. Photo by Justin Merriman for Coffee or Die Magazine.

Aleman’s Van Horn Station is only a small part of a much larger Big Bend Sector, which is itself just a chunk of US Border Patrol’s operations along an international boundary with Mexico that runs 1,954 miles, from the toe of Texas to California’s coastline.

Big Bend Sector takes in 77 Texas counties and the entire state of Oklahoma — 165,154 square miles of mostly wilderness and ranchland. Van Horn is one of its eight stations, all in Texas. There’s also a substation in the sprawling Big Bend National Park.

Aleman’s agents guard 31.1 miles of border with Mexico and patrol all of Culberson County and roughly 50 square miles of neighboring Presidio and Jeff Davis counties. Add it all up and it’s roughly 3,775 square miles, but most of the action begins at the Rio Grande and ends 100 miles north along Interstate 10, where the drug mules were headed.

TFO would move with Aleman and a string of other US Border Patrol agents over the next week, riding from Lobo to Sunland Park, a New Mexico suburb in the El Paso Sector that abuts Ciudad Juárez, the largest city in the Mexican state of Chihuahua with 1.5 million citizens.

On Feb. 23, 2022, south of Van Horn, US Border Patrol Station Patrol Agent in Charge Jose Aleman walks through the West Texas brush. Photo by Justin Merriman for Coffee or Die Magazine.

The trip came during a time of skyrocketing arrests along the border, though not for drug mules. In March of 2022, agents seized only 43,900 pounds of narcotics in all the Southwestern sectors, half of the tally in the same month of 2021.

Instead, they’re facing record numbers of what they call “encounters.” It’s a figure that includes both the migrants who are detained for illegally entering the US and those expelled under Title 42, a federal health measure that’s used to quickly boot undocumented foreigners caught on US soil.

In February of 2022, federal law enforcement in El Paso and Big Bend recorded 23,621 encounters, a number 45% higher than at the same time in 2021.

And with Title 42 slated to sunset in May, US Border Patrol was prepping for a tougher crackdown on the “coyotes.”

In Sunland Park, New Mexico, on Feb. 25, 2022, US Border Patrol Agent Orlando Marrero stares into Ciudad Juárez, the largest city in the Mexican state of Chihuahua, waiting for migrants to cut or hop a barrier wall. Photo by Justin Merriman for Coffee or Die Magazine.

In the borderlands, coyotes are the smugglers who specialize in bringing in people. Some coyotes are foot guides, leading groups of migrants across the desert pan, over ridges like the Sierra Vieja, and around US Border Patrol checkpoints and roving federal agents.

Others run stash houses, clandestine way stations on the path north where migrants can get water and food before moving on, but they’re rare in the Big Bend Sector.

That’s not true in El Paso and the suburbs north of Ciudad Juárez. In 2021, El Paso agents raided 306 stash houses and detained 3,212 migrants found hiding inside them.

In both sectors, the final phase of an unlawful migrant’s journey usually comes in the back of a vehicle gunning for “hub cities,” large metropolitan areas located past the major US Border Patrol checkpoints with road, rail, bus, and air travel out of town.

In El Paso, coyotes eye New Mexico hubs like Las Cruces and Albuquerque. In Aleman’s Big Bend Sector, they’re trying to reach Odessa or Midland, cities roughly 160 miles northeast of his station.

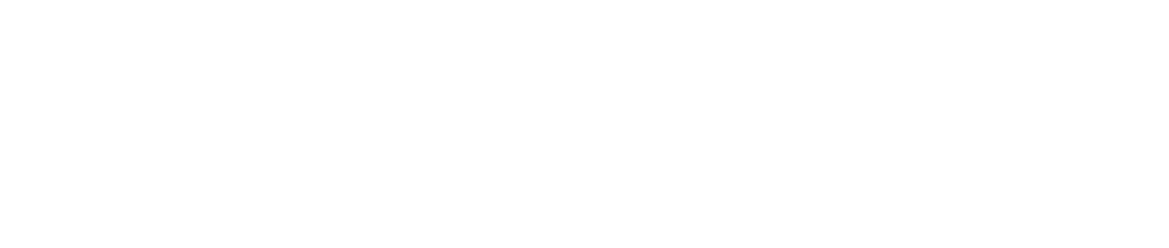

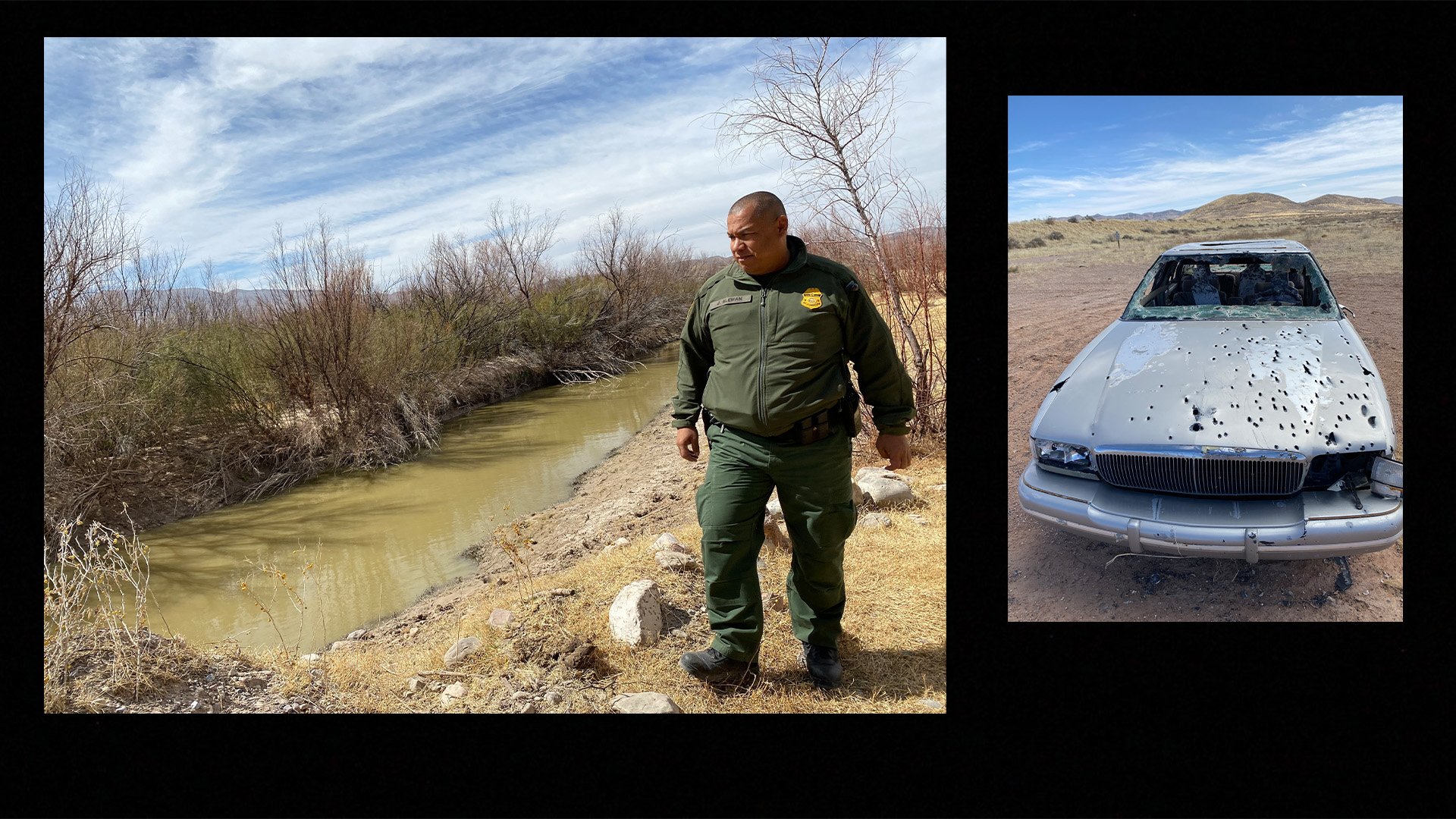

After coyotes lead undocumented migrants over the Rio Grande River, they scoot for the vast wildlands of West Texas until the smugglers hand them off to drivers, who either gun it for hub cities like Odessa or San Antonio or bring them to a series of stash houses to hide from US Border Patrol. They don't always make it. Photos by Carl Prine/Coffee or Die Magazine.

In rural New Mexico and Texas, it’s not unusual for migrants to journey weeks on foot across mountains and desert, drinking brown water out of livestock tanks if they’re lucky, dying of thirst or exposure if they’re not.

Over the previous 12 months, Culberson County Sheriff Oscar E. Carrillo recorded 31 dead migrants. And he knows there are more bodies out there left to the turkey vultures and fire ants. He worries more migrants will die in the coming months, as the weather warms.

But migrants die in the cold, too. Aleman took TFO to a bend of the Chispa Road where a Jeff Davis County rancher on Jan. 27, 2021, found the body of Jose Alfredo Lopez-Vasquez, one of 10 migrants descending the 30-story trail from the top of Needle Peak to the Lower Shutup, a dry gulch of broken basalt, red rock, and cactus snagging at their denim.

Two weeks before Christmas, a federal jury in nearby Pecos convicted Mexican foot guide Pedro Ramirez-Urbina, 41, of leading Lopez-Vasquez into the valley of death.

He was sentenced to six years behind bars. He's appealed the punishment.

After fording the Rio Grande, undocumented migrants might trek for days, even weeks, across scrub and mountains in an effort to dodge US Border Patrol agents. Photos by Carl Prine/Coffee or Die Magazine.

“The smugglers, honestly, many of them have no soul,” said Aleman. “The way they mistreat the people, the way they lie to them. They tell them, ‘You know what? You only need 2 gallons of water. It’s only a one-day trek.’ And, in reality, you need 20 gallons of water to trek over those mountains.

“They abandon the people to pass away. To them, they’re nothing but commodities. They’re soulless.”

But Ramirez-Urbina also was an outlier.

Most coyotes are American drivers, not Mexican guides.

Once undocumented migrants ford the Rio Grande, they'll trek for days, even weeks, through the West Texas brush to rendezvous with drivers who will speed them either to a hub city like Odessa or a series a stash houses, trying to stay one step ahead of roving US Border Patrol agents. Not every driver makes it. Photo by Justin Merriman for Coffee or Die Magazine.

Between the beginning of 2021 and March 6, 2022, federal prosecutors in Pecos charged 84 adults with trying to drive undocumented migrants out of the Big Bend Sector. Sixty-four of the defendants were born and raised in the US, according to court records analyzed by TFO.

The typical driver is 35 years old, and he’s from Dallas, Odessa, Midland, or Lamesa, a small Dawson County town roughly 300 miles north of the border. Very few are locals.

And when they’re pulled over, they’re hauling, on average, 13 passengers stuffed into an SUV, the coyote’s vehicle of choice. More than half of those passengers come from Mexico, but two out of every five began their journeys from a quartet of Central American countries — Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, or Nicaragua.

The typical American driver pockets just under $750 per person and, when caught, draws a two-year federal prison sentence. Nearly all of them plead guilty.

Agent Shay Miller, 29, exited the US Air Force to join US Border Patrol. Photo by Justin Merriman for Coffee or Die Magazine.

US Border Patrol Agent Shay Miller, 29, told TFO about a 3 a.m. vehicle patrol she made south of Marathon. With roughly 400 residents, it’s the biggest town in that part of Brewster County.

Brewster County is three times the size of Delaware, but only 10,000 people live in it. So Miller often finds herself alone on patrol under the shimmer of the Milky Way, waiting for something insane to happen.

“It gets pretty crazy in this job, but that’s the type of stuff that I like. You never know what’s gonna happen. It keeps your adrenaline up,” said Miller, who left the US Air Force as a tech sergeant to become a federal agent, partly because her paycheck tripled.

On that night, she nosed her patrol vehicle behind an SUV that was “packed full of, I think, 18 illegals, so I chased them for over 30 miles by myself.” And that took a long time, because the driver never got over 50 miles per hour, “which was even scarier for me because I was thinking, like, ‘What are they doing? Why are they going so slow?”

US Border Patrol Agent Shay Miller, 29, left a great career in the US Air Force to battle smugglers in the western stretches of Texas. Photo by Justin Merriman for Coffee or Die Magazine.

The driver then suddenly yanked his SUV to the side of the road, and migrants began bolting into the brush, with Miller on their heels.

“So I was just grabbing them and, you know, kind of just throwing them down one by one,” she said.

She got five. Eventually other agents showed up, and their dragnet netted the rest. The driver was from Midland, but he pretended he couldn’t speak English, Miller said.

She tells her story with a few laughs, but it could’ve gone a lot worse.

In rural Texas and New Mexico, coyotes ferrying undocumented migrants inside cars and trucks often speed down rutted roads, trying to stay a step ahead of roving US Border Patrol agents. Photo by Carl Prine/Coffee or Die Magazine.

Of the 84 coyotes arrested for driving migrants over the previous 12 months, seven were caught packing loaded firearms. Ten others were convicted violent felons. And four others were out on parole, or on bond, or had their names tied to active arrest warrants, which often tempts them to fight or flee.

Jose Alejandro Crecencio, 21, of Dallas, pleaded guilty Feb. 1, 2022, to nearly running over two park rangers in Big Bend National Park. Three other coyotes led law enforcement on high-speed chases over the past year, including Jose Luis Lozoya, 31.

That chase ended when the Midland man’s vehicle collided with an elk, spinning him and his haul of migrants off the road and then into the brush. Jeff Davis Sheriff’s deputies found him on March 26, 2021, slumped injured under a tree south of Fort Davis.

His five passengers had been walking through the desert for five days without food or water. He’s serving a 31-month sentence at Florence Federal Correctional Institution in Colorado.

US Border Patrol vehicles will drag tires along a dirt road to create furrows in the dust. Then they'll look for footprints and other sides that smugglers or undocumented migrants have crossed it. Photo by Justin Merriman for Coffee or Die Magazine.

“The penalty for crossing the border should never be death,” said Van Horn’s Aleman.

He told TFO there are too many days when he has to tell his agents, “Every apprehension is a rescue,” because migrants are freezing to death atop a mountain or dying of thirst in the desert below.

The good thing, he said, is that US Border Patrol has never been better at catching coyotes, drug mules, or migrants.

Although former President Donald Trump’s campaign to build a new series of walls across the Southwestern border garnered headlines and votes, agents in both the El Paso and the Big Bend sectors said the fortifications aren’t the most important tool at their disposal.

Aleman stopped his truck along Farm to Market Road 1523 outside Valentine. He pointed into the scrubland and said, “Autonomous surveillance tower.”

Autonomous surveillance towers now pepper the international boundary with Mexico, constantly searching for signs that smugglers or undocumented migrants have crossed into the US. Photo by Justin Merriman for Coffee or Die Magazine.

It was a camera mounted on a pole three stories above the desert. It stares in all directions, day and night, peering across 3.1 miles of ranchland. When migrants move out of its range, another will pick up the scan, following them off the ridgelines and into the flats, where they can be arrested easily.

“We have a lot of that technology out there that detects the traffic,” Aleman said. “They alert us. And then we go out there and we do our thing.”

According to US Border Patrol, more than 200 of the new robot towers pepper the borderlands. They run on renewable energy, usually solar power. And they’re linked to an array of other video surveillance systems towed by trucks or carried high above by drones, blimps, and federal patrol aircraft.

But agents really love the autonomous surveillance towers, whether they’re in the desert or inside busy neighborhoods like New Mexico’s Sunland Park.

An autonomous surveillance tower rises above Sunland Park, New Mexico. US Border Patrol agents credit the technology with turning the tables on smugglers and undocumented migrants trying to sneak across the international boundary with Mexico. Photo by Justin Merriman for Coffee or Die Magazine.

At the top of a hill above the “Two Cups” section of the city, US Border Patrol Agents Carlos A. Rivera and Orlando Marrero can’t stop praising the “ASTs.”

“Game changer,” said Rivera, who’s been an agent for 13 years.

“They automatically detect movement and give you geographical data and everything,” added Marrero, 46, who’s been in the agency as long as Rivera.

Both were raised in Puerto Rico. Marrero doubles as an emergency medical technician on the sector’s elite Mobile Response Team. He told TFO that the camera provides overwatch when he’s patrolling alone along a border wall that’s constantly being breached by coyotes.

The coyotes torch crawl holes in the steel bulkheads or build rebar ladders so migrants can quickly scale them.

“For every 9-foot wall there’s a 10-foot ladder,” said Rivera, pointing at a twisted ladder abandoned on the northern side of a border wall.

US Border Patrol agents are constantly on the lookout for barriers that have been burned open, ripped apart, or scaled by ladders, like this hole in the wall in Sunland Park, New Mexico. Photo by Justin Merriman for Coffee or Die Magazine.

In Aleman’s portion of West Texas, coyotes and drug mules spend weeks walking through the brush to avoid agents. In Sunland Park, the smugglers’ strategy is to fling so many migrants over the fence at the same time that agents must divide their forces to catch them.

If the fence jumpers get past the first line of agents, they stand a good chance of reaching a stash house to hide.

Which is why Rivera ended up bounding over sidewalks and roadways to corner a pair of Guatemalans fresh over the wall. And Marrero dove into a long drainage tunnel to ferret out a third migrant desperately trying to escape into the sewers.

The nabbed migrant’s money and ID went into a zip-sealed bag before other agents folded him into a US Border Patrol paddy wagon, minus his shoelaces.

Rivera said they take the laces to prevent migrants from hanging themselves in a detention cell, but also to keep disgruntled detainees from garroting coyotes who get swept up with them.

In cities like Sunland Park, a New Mexico suburb of El Paso, Texas, US Border Patrol agents try to stop undocumented migrants from reaching nearby stash houses or drivers who will ferry them to hiding spots. Generally, smugglers give migrants three chances to reach a stash house before they're charged a new fee to cross. Photo by Justin Merriman for Coffee or Die Magazine.

He estimates one in every three migrants they encounter surrenders and asks for an asylum hearing. The rest run, but agents are catching more than 500 here every day.

Smugglers give migrants three chances to make it to a stash house. If they return to Mexico after three failed attempts, they have to pay to be smuggled again. But the agents figure they catch far more migrants than get away.

Emilio Delacruz, 29, was one of them. He told TFO he paid smugglers 120,000 pesos — about $6,000 — to bring him from the southern tropical state of Chiapas to El Paso, where he’d worked in the past as a night nurse for a Texas family.

“I love it here,” he said in Spanish. “I was going to take care of a patient, as a nurse. I wanted to do everything legally, but I couldn’t. So I just tried to come across.”

Emilio Delacruz, 29, told Coffee or Die Magazine he paid smugglers 120,000 pesos — about $6,000 — to bring him from the southern tropical state of Chiapas to El Paso, where he’d worked in the past as a night nurse for a Texas family. Photo by Justin Merriman for Coffee or Die Magazine.

TFO asked him to name the smugglers.

“No, I won’t rat them out,” Delacruz said.

Which is probably smart because coyotes work — directly or indirectly — for large and often ruthless Mexican cartels. And they’ll murder a chatty migrant.

Across from El Paso, the Juárez cartel controls the underworld. In Mexico, across from Aleman’s station, the Juárez and Sinaloa cartels are waging a brutal war over the lucrative narcotics and human smuggling routes into Texas.

And at the far eastern edge of Aleman’s sector, Los Zetas run the ratlines into Texas. They’re outlaws renowned in the borderlands for indiscriminate massacres, beheadings, torture, and corrupting cops and politicos.

Supervisory Border Patrol Agent Jose Angel Vasquez is an operator assigned to the elite Border Patrol Tactical Unit, better known by its shortened name, BORTAC. Photo by Justin Merriman for Coffee or Die Magazine.

Supervisory Border Patrol Agent Jose Angel Vasquez, 37, has been battling all three cartels since he was 26. And until now, you’ve probably never heard his name.

That’s because he’s an operator in the S-3, the operations staff for the agency’s secret Border Patrol Tactical Unit, better known by its shortened name, BORTAC. It’s headquartered at Biggs Army Airfield on Fort Bliss in El Paso, although its clandestine operations span the globe.

BORTAC is what his agency calls a “national asset,” which means its highly trained operators deploy to the hottest spots on the US borders, with a focus on cracking the cartels when their smugglers move people or drugs north of the Rio Grande, or confiscating their guns and money before they go south.

“For us, I mean, you can try to catch as many people or as many pounds of marijuana or as many aliens as you want,” said Vasquez. “But until you start affecting that supply chain, that’s when you start really affecting some of these organizations. And so what we found is, you start catching a driver, you start catching stash houses, start catching facilitators and start getting where that money’s at, that’s when you start seeing the real impact.”

From left: US Border Patrol Agents Matt Young, Zach Bressler, and Jesse Serio are operators assigned to the elite Border Patrol Tactical Unit, better known by its shortened name, BORTAC. Photo by Justin Merriman for Coffee or Die Magazine.

The team was launched in 1984 to quash riots inside US Immigration and Naturalization Service brigs. It’s since morphed into a cross between SWAT and Navy SEALs, with a Selection and Training Course that mirrors the training programs run by US special operations forces.

BORTAC, said Vasquez, is “the best-kept secret in America.”

The Texas gunman who killed 19 children and two teachers on May 24 at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde was shot to death by a BORTAC special operator, officials told TFO.

The agent was part of a Del Rio-based team working west of San Antonio in an ongoing campaign taking down stash houses when the rampage at the school began. Texas authorities identified the dead gunman as 18-year-old Salvador Ramos, a student at Uvalde High School. Investigators believe the teen also shot his grandmother before beginning the massacre.

An undocument Guatemalan migrant is detained in Sunland Park, New Mexico, on Feb. 25, 2022. He'd scaled a border wall abutting Ciudad Juárez, the largest city in the Mexican state of Chihuahua. Photo by Justin Merriman for Coffee or Die Magazine.

Vasquez told TFO the typical indoc class loses between 70% and 80% of its candidates. He made BORTAC seven years after he joined the US Border Patrol, and he said he was “one of the lucky ones” who passed on his first try.

Nationwide, there are only 225 BORTAC operators. Border Patrol Search, Trauma, and Rescue — or BORSTAR, a unit that specializes in daring rescues and medical evacuations — has roughly the same number of agents. And they’re overseen by 150 Special Operations Group staffers and supplemented by 485 Mobile Response Team agents in sectors nationwide. BORTAC operators also often work side by side with teams from the US Department of Homeland Security, the FBI, the DEA, and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives.

In late February, Vasquez stood with TFO, watching Phase II training at Bliss, his agents rushing through popped smoke canisters and firing their M4 carbines. While they blazed away, he rattled off the numbers: 190 agents applied to BORTAC’s training course; 77 were invited to selection; 18 made it through the initial phase; only a dozen remained.

When they graduate, they’ll be earmarked for serving high-risk arrest warrants; sniping; running complex intelligence, reconnaissance, and surveillance operations or airmobile and maritime raids; and working alongside foreign law enforcement agencies.

Over the past two decades, that included tours in Iraq and Afghanistan.

A crude rebar ladder lies crumpled in the dirt of Sunland Park, New Mexico, on Feb. 25, 2022. Migrants use these ladders to scale border walls abutting Ciudad Juárez, the largest city in the Mexican state of Chihuahua. Photo by Justin Merriman for Coffee or Die Magazine.

In the past, the feds required agents to serve two years as agents in the field before trying out for BORTAC. But Vasquez said he’s now “actively giving waivers” to very “highly qualified” applicants, by which he means veterans of elite military and police units.

A SEAL, Green Beret, Marine Raider, or Army Ranger?

“I would actually almost guarantee that we would give him a waiver, for sure,” Vasquez said, quickly adding that US Border Patrol’s larger Special Operations Group also needs linguists, people with “intelligence backgrounds,” and college grads with high-tech degrees.

Transitioning vets just need to know that they’re joining a culture of “quiet professionals,” he said, a group of elite agents who don’t let their BORTAC insignia go to their heads. They’ll be working alongside rugged, physically fit agents, often in remote corners of America’s wildlands, for the same pay as fellow agents watching the Rio Grande.

Undocumented migrants are detained in Sunland Park, New Mexico, on Feb. 25, 2022. They had scaled the border wall abutting Ciudad Juárez, the largest city in the Mexican state of Chihuahua. Photo by Justin Merriman for Coffee or Die Magazine.

They volunteer for some of the worst jobs along the border.

“Well, it’s the middle of winter. We need someone to go sit up on a mountain and do LP/OP operations, like, all right? Well, you’re gonna have to keep guys away from doing it, because the guys are gonna volunteer,” Vasquez said.

Agents Matt Young and Zach Bressler were wrapping up their BORTAC training at Bliss in late February. Agent Jesse Serio was one of their instructors.

All three were noncommissioned officers in the military combat arms before they joined the agency. All three said the military helped prepare them for US Border Patrol’s training academy and, later, special operations.

Undocumented Guatemalan migrants are detained in Sunland Park, New Mexico, on Feb. 25, 2022. They had scaled the border wall abutting Ciudad Juárez, the largest city in the Mexican state of Chihuahua. Photo by Justin Merriman for Coffee or Die Magazine.

Bressler, 27, a Marine infantry veteran who worked his way up to sniper, said too many grunts default to a “bullshit” plan to go to college when they get out, and “they’re not going to do that, because it’s not a real plan.”

“That’s just a cookie-cutter plan,” he said. “So I would just say, like, really think hard about what you want to do afterwards. And like this. It doesn’t have to be the Border Patrol. But any federal agency is just, like, at least have that outline in your head. That it’s just an option.”

A former US Army paratrooper with tours in Iraq, Afghanistan, Haiti, and Hungary, Young, 34, said he was drawn to BORTAC because the operators are “self-starters,” like all good NCOs, and he loves working outdoors.

Serio, 44, is a former joint fire support specialist in the New York Army National Guard who joined US Border Patrol in 2006 after fighting in Iraq. He told TFO he’d “do this for half the money.”

“I mean, it’s a great job. You’ve got to love your job,” said Serio, who passed BORTAC indoc in 2010.

“Catching dope, catching bodies, working smuggling cases, but then also trying to take whatever we’re working on, developing intel and taking it to the next level,” he said. “We’re not just taking trophy shots with the bundles of dope, or the load vehicle that we got, but, like, actually trying to effect change. Next step. Next step is we’re killing the network, dismantling the network, and taking it to that next step.”

Drug mules and undocumented migrants hiking through the West Texas brush can go days, even weeks, without water. Sometimes, they siphon off water intended for ranch cattle. Photo by Justin Merriman for Coffee or Die Magazine.

Station Patrol Agent in Charge Jose Aleman nudged his boot against a water bottle left in the dirt off I-10 east of Van Horn. Needlegrass speared through the folds in abandoned blankets. The sun was setting on tube socks wrapped around the woolly foot grass, chucked long ago by migrants ditching everything they carried to squeeze into SUVs to Odessa.

“There’s only so much space for bodies. They have to leave their crap behind,” he said.

Across the highway is a culvert. On Nov. 18, 2017, US Border Patrol Agents Stephen Garland and Rogelio Martinez were walking in the dark. It was a 9-foot drop to the hard concrete below.

Garland’s fall knocked him out, and he told investigators he couldn’t remember what happened next. Martinez was found nearby. He died the next day in El Paso. He was 36 and left behind a fiancée and an 11-year-old son.

When drug smugglers or undocumented migrants reach a rendezvous point to meet the coyotes who will drive them to stash houses or straight to hub cities, they'll drop their blankets, water supplies, and dirty clothes in the brush. Photo by Justin Merriman for Coffee or Die Magazine.

The case remains shrouded in mystery. An FBI probe failed to turn up evidence that Martinez was murdered by migrants or coyotes hiding in the culvert, but it also didn’t prove an accidental fall killed him.

Culberson County Sheriff Carrillo has long insisted it was a tragic accident, and blamed “politics from people who don’t live here” for ginning up rumors that foreigners stoned Martinez to death. He said many Americans up north don’t really understand how it all works in the borderlands.

“There’s a big disconnect. It’s a political narrative. You need to live it and see it,” he told TFO.

The memorials left to Martinez in the wash take no side in the dispute, but it’s a special place for Aleman to come.

Standing there, he said little. Above him, the sun dripped into the rimrock of the Sierra Vieja, like the tallow of an orange and purple candle melting into the Texas night. In Spanish, they’re the “Old Mountains,” and he’s now an old lawman, and it was twilight, both for our day in the brush and Aleman’s long career as a federal agent.

He said he’s retiring around November, five years after Martinez’s death.

And then he talked a little more.

On Nov. 18, 2017, US Border Patrol Agents Stephen Garland and Rogelio Martinez fell into a culvert near Van Horn, Texas. Martinez was found nearby. He died the next day in El Paso. Composite by Coffee or Die Magazine.

Aleman spoke into the wind about an armed standoff in Van Horn six days before Christmas in 2021, how he relied on sign cutting to track the prints left by a Mexican migrant who got the drop on a Culberson County sheriff’s deputy.

Aleman had followed the Christmas trees left by the man’s soles across the desert and down alleyways, into a tiny restaurant. Cornered, the man put a 9mm pistol to his own head. Aleman thought it might be a Beretta, maybe a Taurus. Whatever it was, the man in the New Mexico State University T-shirt was screaming he was going to shoot himself with it.

Deputies and Texas troopers raised their pistols, too.

“I didn’t want us to kill him. I didn’t want us to shoot him, because the last thing I want is for him to point the gun,” said Aleman, who wasn’t wearing body armor that night because he took the call when he was off-duty.

“Honestly, I thought he was gonna put it in me or other guys. And we were gonna have to do it. We’ll have to do it. Yeah. And I’m thinking, ‘Man, I’m gonna get shot.’ I’m actually, at that time, like 11 months from retiring. I’m like, ‘Oh, God. I’ve heard the stories, right? The guy’s about to retire. And then this happens.’ I think, ‘I’m only 11 months from retiring and I’m gonna get killed.’ ”

US Border Patrol Station Patrol Agent in Charge Jose Aleman checks for signs of human smuggling near Van Horn, Texas, on Feb. 23, 2022. Photo by Justin Merriman for Coffee or Die Magazine.

Aleman’s parents were from Mexico. He grew up in migrant farm worker camps from the Corn Belt to the Carolinas. He got green tobacco sickness at 14, cutting leaf in a North Carolina field. He wasn’t wearing gloves, and the nicotine in the dew seeped into his blood.

He toiled in a Des Moines hotel before he became a whiz at eyeballing fingerprints for the US Immigration and Naturalization Service, which prepped him to apply for Border Patrol.

He rose all the way from field hand to running a US Border Patrol station. And now he was going to die in a desert town diner.

“Life is too short for regrets,” Aleman told TFO. “Because if you just think about regrets, you don’t think about the future, constantly thinking about regrets. Things happen. They happen for a reason.”

He figured God had a reason for making him talk to this man with a gun. They started by exchanging names, then kept talking for another 50 minutes.

US Border Patrol Station Patrol Agent in Charge Jose Aleman searches for signs of human trafficking near Van Horn, Texas, on Feb. 23, 2022. Photo by Justin Merriman for Coffee or Die Magazine.

“Hey, I’m just like you, Hispanic. My parents are from Mexico,” Aleman remembered telling Pablo Hector Galaviz-Lopez, 27. “I asked him about his parents. He told me a little bit about them and I built a rapport.”

Galaviz-Lopez had panicked because he was facing his third felony reentry prosecution. He’d walked across the bridge from Laredo into Mexico only 18 days earlier, shortly after he was released from a 14-month prison sentence for the same charge.

He was convicted in 2018, too.

Aleman suspected Galaviz-Lopez was a coyote hired by smugglers to guide the migrants past his agents. But they’re almost never armed.

Aleman reminded him Christmas was “just around the corner,” and what would it do to his parents, in Mexico, learning “that you just got shot right before Christmas?”

US Border Patrol Station Patrol Agent in Charge Jose Aleman checks for signs of undocumented migrants crossing the Rio Grande River in West Texas on Feb. 23, 2022. Photo by Justin Merriman for Coffee or Die Magazine.

And then it was over. Galaviz-Lopez appeared to rack his pistol and put it on the table. His hands went into the air. Law enforcement rushed to the table and cuffed him.

Aleman thanked him, sincerely, for not making the agents, troopers, and deputies shoot him, “because we were gonna shoot you.”

And then Aleman looked at the gun. And like a lot of things he sees on the border, it just didn’t look right.

“Anyway, the gun was an airsoft gun.”

This article first appeared in the Summer 2022 print edition of The Forward Observer, a special publication from Coffee or Die Magazine.

Read Next: Dispatch From Syria: Democratic Forces Prepare for Turkish Invasion

Carl Prine is a former senior editor at Coffee or Die Magazine. He has worked at Navy Times, The San Diego Union-Tribune, and Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. He served in the Marine Corps and the Pennsylvania Army National Guard. His awards include the Joseph Galloway Award for Distinguished Reporting on the military, a first prize from Investigative Reporters & Editors, and the Combat Infantryman Badge.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.